Historic Landmarks

The City of Albuquerque designates historic landmarks to help preserve buildings important to a historic person, time period, or event. Click the name of the City Landmark below to read more about its significance.

| City Landmark | Address | Architect / Person of Significance | Year of Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aldo Leopold House | 135 14th Street NW | Aldo Leopold |

|

| Anson Flats | 816-894 5th NW | Anders Anson |

1910 |

| Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Memorial Hospital | 806 Central SE | E.A. Harrison | 1926 |

| Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Passenger Depot (Demolished) | 314 First SW | Charles Whittlesey | 1902 |

| Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Locomotive 2926 | 1833 8th NW | Baldwin Locomotive Works of Philadelphia | 1944 |

| Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Fire Station | First/Second SW | E.A. Harrison | 1920 |

| Barelas Community Center | 801 Barelas Road SW | A.W. Boehning | 1942 |

| Bataan Memorial Park | 3401 Lomas NE | 1943 | |

| De Anza Motor Lodge | 4301 Central NE | 1939 | |

| El Vado Motel | 2500 Central SW | 1937 | |

| Ernie Pyle House/Library | 900 Girard SE | Mount and McCollum, Builders | 1940 |

| Heights Community Center | 823 Buena Vista SE | Alvin Emrick, Building Foreman | 1938 |

| Highland/Hudson Hotel Building | 202 Central SE | Francis W. Spencer | 1905 |

| Historic Fairview Cemetery | 700 Yale Street SE (northern portion) | 1881 | |

| Jones Motor Company | 3226 Central SE | Tom Danahy | 1939 |

| KiMo Theater | 423 Central NW | Carl Boller | 1927 |

| La Posada de Albuquerque | 125 Second NW | Anton Korn | 1939 |

| Las Mañanitas | 1800 Rio Grande NW | Mid-19th Century | |

| Main Public Library | 501 Copper Avenue NW | George Pearl of Stevens, Mallory, Pearl, and Campbell (SMPC) Architects | 1975 |

| Occidental Life Insurance Building | 305 Gold SW | Henry C. Trost | 1917 |

| Old Airport Terminal | 2920 Yale SE | Ernest Blumenthal | 1939 |

| Old Albuquerque High School | Central/Broadway NE | George Williamson, Louis Hesselden | 1914, 1927, 1938-40 |

| Old Main Library | 423 Central NE | Arthur Rossiter | 1925 |

| Roosevelt Park | Coal/Spruce/Sycamore SE | C. Edmund "Bud" Hollied | 1933 |

| Rosenwald Building | 320 Central SW | Henry C. Trost | 1910 |

| Skinner Building | 722 Central SW | A. W. Boehning | 1931 |

| Sunshine Building | 120 Central SW | Henry C. Trost | 1924 |

| The Whittlesey House | 201 Highland Park Circle SE | Charles Whittlesey | 1903 |

Aldo Leopold House

135 14th Street NW

The Aldo Leopold House, constructed for the Leopold family in 1916 and occupied that fall, is located in the Huning Place subdivision. In the mid-1910s, this area was on the western edge of the burgeoning suburbs west of Albuquerque’s downtown. The location offered the Leopold family convenient access to the electric streetcar system running a block north along Central Avenue and was within walking distance of downtown.

The Leopold family lived in the house for nearly a decade, during which Aldo Leopold began developing the ideas that would later underpin his advocacy for preserving natural areas for their scenic and wild qualities. Referred to as the Land Ethic his work helped shaped conservation policies in New Mexico, leading to the designation of areas like the Gila Wilderness, the first designated wilderness area in the United States, which remains a vital part of the state’s natural heritage.

Anson Flats

816-894 Fifth NW, 1910, Anders Anson

Anson Flats, built in 1910, was the oldest remaining apartment building in Albuquerque. It was built and originally owned by Anders W. Anson, a general contractor and cement supplier. Anson constructed several other significant Albuquerque buildings: the Alvarado Hotel, Santa Fe Railroad Depot, Rosenwald Building and the Old Post Office at 4th and Gold.

At the time these apartments were built, Albuquerque was growing due to the impact of the railroad, New Mexico was nearing statehood and new building materials and styles were being imported from the East. Anson's design is reminiscent of row houses in eastern cities such as New York and Baltimore. The building's exterior appearance, highlighted by the rough-textured concrete walls and columns and repeating pattern of porches, made a strong statement about Albuquerque's interest in being thought of as more than a sleepy railroad town in a western territory. While many of the houses built at this time around downtown reflect this interest, Anson is a singular example of this influence on multi-family design.

Anson Flats was severely damaged by fires in 1989, 1992, 1993, and 1995. Its landmark designation was initiated in response to a demolition threat. The building was in the process of renovation and rehabilitation when a final fire damaged the building beyond repair.

The building was finally demolished in 1996, and a new housing has been erected in its place called the Anson Townhomes.

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Memorial Hospital

806 Central SE, 1926, E.A. Harrison

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Memorial Hospital was built in 1926 to serve the railroad's employees by providing emergency medical and health care. It was one of the last buildings constructed by the railroad in Albuquerque, and was one of 13 hospitals AT&SF built along its route from Chicago to Los Angeles. At the time of its construction it was the largest hospital in the state of New Mexico.

The site originally contained three buildings, the most significant being the masonry hospital built in the Italianate style and now home to the Hotel Parq Central. There is also the ancillary SANS building (Nurses and Physicians residence) in the Mediterranean style and the mechanical building housing the original boilers. The protection of these buildings and their detailing is included under its Landmark status.

The hospital remained operational until 1982 when it was closed. It was subsequently used by various health related entities until 2007 at which time its conversion to a luxury hotel began. In 2011, the City of Albuquerque named the AT&SF Memorial Hospital building a City Landmark.

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Passenger Depot (Demolished)

314 First SW, 1902, Charles Whittlesey

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Passenger Depot was destroyed by fire on Jan. 4, 1993. It was built in 1902 along with the now-demolished Alvarado Hotel, and served rail passengers as the gateway to Albuquerque and the Southwest for over 90 years.The depot was built in the California Mission style, which was used extensively by AT&SF designers throughout the West. It sported a domed tower and red tile roof and was surrounded by an arched arcade similar to those found on the neighboring Alvarado. Both the Telegraph Office and the Depot were made with pebbledash stucco (a bit like pebbles covered with a thick glaze) that was common from 1900 to 1925, and the Telegraph Office remains an excellent example of this kind of stucco.

Dignitaries such as Theodore Roosevelt and Clark Gable passed through the terminal along with thousands of others traveling to the West Coast or visiting popular sites throughout New Mexico.

Three later depot-area buildings—the Freight House, Telegraph Office and Curio Storage Building—along with a trackside wall of the Alvarado complex remain as reminders of the glory days of rail traffic through Albuquerque.

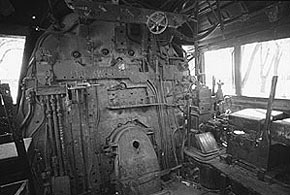

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Locomotive 2926

1833 8th NW

Topeka and Santa Fe Locomotive 2926 is representative of the last steam locomotives used by the Santa Fe Railway. The locomotive was built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works of Philadelphia and began its service for the Santa Fe in 1944.

It hauled mostly freight trains until the end of World War II, when it began passenger service between Chicago and the West Coast. Most trips were with the railroad's Grand Canyon and California Limited trains, although 2926 also served the Chief and El Capitan runs.

The 2926 Locomotive has a 4-8-4 wheel configuration (four pilot wheels, eight main "driving" wheels, and four trailing wheels), which is the mostly technically advanced of the final days of the steam locomotive. The 2900 class of steam locomotives was known not only for its physical size and power, but also for the ability to make extended runs without roundhouse attention. The locomotive itself weighs over 510,000 pounds. Its tender had the capacity for 24,500 gallons of water and 7,000 gallons of fuel. Fully loaded, the locomotive and tender weighed over 975,000 pounds.

The 2926 made its final run on Dec. 24, 1953, from Clovis, in New Mexico's eastern plains, to Belen, south of Albuquerque. In nine and a half years of service it logged 1,090,589 miles. The Santa Fe Railway donated 2926 to the City of Albuquerque in 1956, and it stood in Coronado Park until June 2000, serving as a reminder of the glory days of passenger rail service and the importance of the railroad in Albuquerque's history.

It was recently sold to the Albuquerque Locomotive and Rail Historical Society, a New Mexico non-profit corporation, for $1 to remove any hazardous materials and restore the locomotive into possibly operating condition. In the agreement, the locomotive, tinderbox, and caboose (not officially included in the city landmark) were moved in June 2000 to a temporary storage location until it can be moved to a restoration facility. As a Landmark, all the details exemplary of the 2900 class steam locomotives must be preserved.

Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Fire Station

First/Second SW, 1920, E.A. Harrison

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Fire Station was built in 1920 to serve the railroad's shop and roundhouse complex, located south of the passenger depot and Alvarado Hotel. It was one of the last buildings constructed by the railroad in Albuquerque, and reflected the company's interest in providing independent services and utilities for its operations.

This is Albuquerque's oldest remaining fire station. Its rustic architecture is rare in the city, conveying the railroad architect's romantic images of the Southwest. E.A. Harrison's design features a rough, sandstone exterior with an asymmetrical tower, crenellated parapet and sleeping porch.

The tower itself is decorated with tiled overhangs, protruding beams, a stone insignia and ornamental globes. The building's sandstone, quarried at Laguna Pueblo, was taken from a demolished 1881 roundhouse built by the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, a forerunner to the AT&SF. The protection of all of these features is included under its Landmark status.

The fire station was used as offices for several years following the demolition of the roundhouse. It is currently vacant but still stands as a reminder of the important role that the AT&SF industrial complex played in Albuquerque's economy through most of the 20th century.

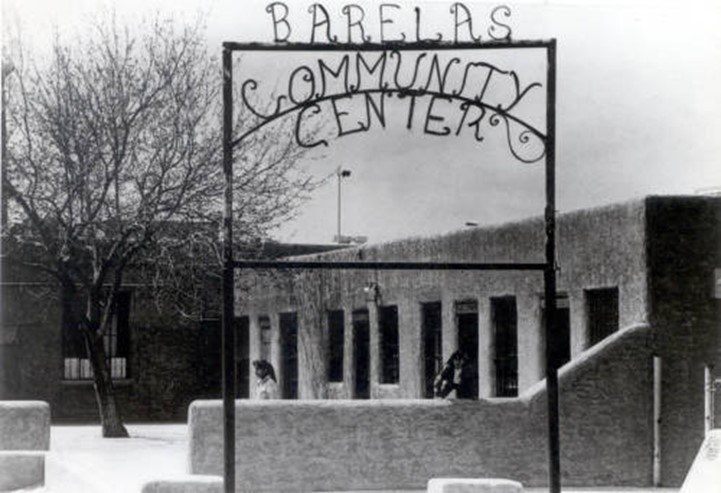

Barelas Community Center

801 Barelas Road SW

Constructed in 1942, the Barelas Community Center stands as an intact example of Spanish-Pueblo Revival architecture. The architectural vision of A.W. Boehning, an Albuquerque-based architect, brought this stucco-covered adobe block building to life with distinctive features such as battered walls, rounded parapets, flat roofs, and recessed fenestration, all contributing to its imposing presence. The construction involved active participation from Barelas residents and individuals enrolled in the National Youth Administration program.

Despite some modifications, the community center strongly reflects Spanish-Pueblo Revival architecture, showcasing the characteristic design, materials, and craftmanship associated with the style. The center retains integrity of location, setting, feeling, and association. In its original location on Barelas Road, the open, outdoor recreational space associated with the center remains, contributing to a park-like setting.

Bataan Memorial Park

3401 Lomas NE between Amherst & Tulane, 1943

In 1941, 1,800 men from the 200th and 515th Coast Artillery Regiment, mostly men from New Mexico, deployed to the Philippines to partake in war simulations. Within 3 months the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor and invaded the Philippines. After four months of fierce fighting, the Japanese broke through Allied lines. This led to the eventual fall of Bataan peninsula and the death march to confinement camps. Of the 1,816 men 200th & 515th Coast Artillery men identified, 829 died in battle, while prisoners, or immediately after liberation. There were 987 survivors.

In 1943, the City of Albuquerque dedicated the Bataan Memorial Park with a resolution that reads, in part, as follows: “The people of Albuquerque desire, in a spirit of humility, to pay tribute to its soldiers, both living and dead, who served so nobly, that their deeds and sacrifices shall forever be etched in the memories of the people of the community which they left for so valiant service to their country.”

The desire to preserve the historical integrity of the park resulted in it being placed on the New Mexico State Register of Cultural Properties in 1999. On November 11, 2012, the City of Albuquerque dedicated Bataan Memorial Park as a City Landmark.

De Anza Motor Lodge

4301 Central NE, 1939

De Anza Motor Lodge represents one of the Route 66 motor lodges that depict a time in history when the American people took to the open road. These motor lodges offered a clean place to stay, some rooms having individual carports.

The De Anza was built by C.G. Wallace, a long time trader with the Zuni nation, in 1939. He utilized the hotel as a place to display and sell the jewelry of the Zuni whose pueblo had been circumvented by the new highway. It was initially designed in the Pueblo style with exposed vigas, wide overhangs and battered walls and was considered an ultra-modern tourist court with showers and steam heat, private telephones and air conditioning in each room. It was also one of the few hotels in the area listed in the Green Book, a guide to black travelers of the day, that told them of hotels and restaurants where they would be welcome.

After World War II, Wallace updated the Lodge to bring in more travelers. He added more rooms and a café called the Turquoise Room. In a basement conference room he had the Zuni painter Tony Edaakie paint a mural depicting the Shalako procession. The City of Albuquerque purchased the motel in 2003 to save it from demolition and is working with private developers to create a viable project and preserve the Zuni murals. The building was added to the New Mexico State Register of Cultural Properties in 2003 and the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. In 2012 it was made a City Landmark.

El Vado Auto Court

2500 Central SW, 1937

El Vado Motel is one of the best examples of a largely unaltered pre-WWII tourist court remaining along Route 66. It was built along Central Avenue in 1937 in anticipation of the rerouting of Route 66 East/West through Albuquerque. Its Spanish Pueblo Revival architecture still remains intact with its painted vigas and white stucco adobe walls. It is the oldest motor court along the West Central Avenue strip.

The setting, location, design and materials of the El Vado reflect early tourist court construction in New Mexico. Its extensive use of the Pueblo Revival style recalls the emphasis often placed on regional styles in the 1930s

Efforts are currently underway for the retrofitting of the El Vado. This new project incorporates the existing motel with renovated guest rooms and mini suites, food pods, an amphitheater and a new events center. This is a welcome addition to the economic revitalization of the area.

As recently as 2005, the motel was proposed for demolition and construction of townhouses. Seeing it as a cultural asset to the City, the El Vado was designated as a City Landmark in January 2006. To ward off demolition, the City purchased the property in 2010. In 1993, it was listed on both the State and National Registries of Historic Properties.

Ernie Pyle House/Library

900 Girard SE, 1940, Mount and McCollum, Builders

Ernie Pyle and his wife, Jerry, had this house built after years of roving the Americas for Ernie's work as a syndicated columnist. Both hailed from the Midwest but chose Albuquerque for a home after visiting many times and developing, in Pyle's words, "a deep, unreasoning affection" for New Mexico and befriending Edward Shaffer, editor of the Albuquerque Tribune, and his wife, Liz.

Pyle's stories of the people and places he and Jerry visited across the Americas had made him famous by 1940. But it was his personal, soldier-oriented dispatches from military theaters overseas, read avidly by millions during World War II, that brought him high acclaim and, in 1942, a Pulitzer Prize for distinguished war correspondence.Wartime work and travel kept Pyle far from home for months at a time, and some of his columns mentioned Jerry and the little white house and picket fence back in Albuquerque.

Ernie Pyle was killed in action by a sniper on a Pacific island in April, 1945. Four months later the war ended, and Jerry died later that year. The City of Albuquerque acquired the house from the Pyle estate and in 1948 opened it as a branch library. Ever since, the City has preserved it carefully and displayed Ernie Pyle memorabilia alongside the library's books. Visitors come from the neighborhood, all the United States, and many other countries.

Since the history behind the house is its most significant feature, and its conversion to a library has preserved the general character of the house and all its details, any future restoration or rehabilitation should reflect that character. Both the interior room configuration and the landscaping, even the picket fence built by Pyle and the grave marker of their dog, Cheetah, must be preserved to reflect the history and time period of its owner.

Heights Community Center

823 Buena Vista SE, 1938, Alvin Emrick, Building Foreman

Heights Community Center was the first community recreation center in the city and has served generations of Albuquerque residents. It was constructed between 1938 and 1942 as a National Youth Administration Project, one of several New Deal programs active in Albuquerque during the Great Depression. NYA projects were intended to give youth thorough vocational training and revive their interest in education. At the time, it was considered the largest NYA project in the country. Much of the work for the center was carried out by volunteers using donated or salvaged materials.

Several different civic groups in the Heights thought up the idea of a community center, and had land available and raised about $100, but not enough to secure the funding needed to make the center a reality. The NYA had been organized and was looking for a first project, and brought $20,000 to the project, but it wasn't enough for the cost of materials for construction. So, the boys working through the NYA program made adobes on site, and many other materials were scrounged from schools being torn down around that time.

Since its opening, the center has been a popular location for community events. During World War II, servicemen stationed in Albuquerque for training flocked to dances at the center. Folk, square, and swing dancing groups still actively use the center's wooden dance floor, which many consider the best in the area. As a Landmark, the wooden dance floor, in addition to all of the southwestern detailing, will always remain intact.

It was modeled after an historic Spanish courtyard house type, features an inner courtyard ringed by a portal with rough-hewn log columns, heavy beams, corbel brackets and vigas. Southwestern design details can also be found along the front façade and throughout the building's interior, particularly in the ballroom, which includes corner fireplaces, bancos, and exposed vigas, as well as the wooden dance floor.

Highland/Hudson Hotel Building

202 Central, 1905, Francis W. Spencer

Business buildings used to line Central Avenue to Broadway, a natural extension of downtown Albuquerque. Now, the Highland Hudson Hotel Building is all that is left of the Victorian business blocks east of the railroad tracks. The exposed brick façade with its arches, pilasters and cornice line reflect the building's roots in Chicago. The detailing is flat and not overly ornate, like many of the skyscrapers that were built around that time in the Midwest. It is now one of the few buildings left in Albuquerque of that time, which is why the façade is one of the significant features the city wished to protect under its landmark status.

This three-story brick building was built in 1905 to replace the brick and wood Highland Hotel which burned down in a spectacular blaze in 1903: liqueurs in the bar tinted the flames a rainbow of colors. The new hotel was designed by Francis W. Spencer, reported to have also designed the old public library at Edith and Central. It was termed "one of the handsomest commercial edifices in the city" and expected to be "an architectural ornament to that part of the city where the ruins of the old hotel have long been an eyesore."

The new building had rooms for guests on the top two floors, catering to salesmen traveling on the Santa Fe Railway. The first floor was rented out for commercial use; whenit first opened, the French Bakery and the Sanitary Market occupied the space. In 1924 Peter and Stella Hudson bought and renamed the hotel, but they only remained as owners until 1927. The building operated as an economy hotel, with commercial space on the ground floor, until 1976. In the early 1980s the architectural firm Hutchinson Brown Partners, gave the hotel new life when they renovated it for use as offices. The building now serves as the centerpiece of a small commercial district. The first floor storefronts are essential to the character of this building and are one of the key elements that will be preserved now that it is a city landmark.

Historic Fairview Cemetery

700 Yale Street SE (northern portion)

Historic Fairview Cemetery, holds a unique place in Albuquerque’s heritage. Established in 1881, this cemetery is the final resting place for generations of local residents, including many who shaped the early history of New Mexico. Spanning over 17 acres, Historic Fairview Cemetery showcases beautiful landscapes and diverse memorials, reflecting Albuquerque’s cultural and historical evolution. With its mature trees, historic gravesites, and pathways, this site offers a peaceful haven and a meaningful glimpse into the past.

Jones Motor Company

3226 Central SE, 1939, Tom Danahy

The Jones Motor Company was originally a gas station, car dealership, and repair shop that served motorists along Route 66 and the early suburbs on the East Mesa. Ralph Jones, the founder and president of the dealership, was a big advocate in promoting Route 66. He was the President of the Route 66 Association, President of the Chamber of Commerce, and the Chairman of the New Mexico State Highway Commission during the late 1940s.

Architect Tom Danahy designed the building for Jones in 1939. Danahy is also known for his design of the El Rancho Market for Barber's grocery chain, at Yale and Central. Because of his connections to many of the richer families in Albuquerque, he also designed many of their homes mostly in the Country Club area in the '30s and early '40s.

The Motor Company was built on a corner, so it would be accessible from two sides, and had gas pumps at an angle to the building, so motorists could drive up to them easily. Later two buildings were added, one completely separate one in 1942 and the canopy in 1951? The building has several features associated with the Moderne style, including the stepped tower over the central part of the building and the curved walls.

Since its life ended as a service station in 1957, the building housed many other retailers, including a Goodwill and Furniture mart. In 2000, after being vacant for several years, Kelly's Brewery restored the building and converted it into a restaurant and brewpub. They returned much the building to its original design, including adding a Texaco gas pump in the front and preserving the garage doors.

KiMo Theatre

423 Central NW, 1927, Carl Boller

The KiMo Theatre opened in 1927, fulfilling Albuquerque merchants Oreste and Maria Bachechi's dream of providing an opulent movie palace based on southwestern design themes. The Pueblo Deco showcase was designed by Carl Boller of Boller Brothers, a Kansas City architectural firm active in movie-house design throughout the west during Hollywood's early days of popularity.

Isleta pueblo Governor Pablo Abeita won $500 for suggesting the name, which means "king of its kind." Construction cost $150,000, with an additional $18,000 to provide a Wurlitzer organ to accompany the silent movies. Construction was completed in less than a year. A luncheonette and a gift shop were located in spaces adjacent to the theatre entry. After Oreste Bachechi died, his sons took over theatre, combining vaudeville and out-of-town road shows with movies.

The KiMo borrowed motifs from many of the pueblos surrounding Albuquerque, as well as from Navajo imagery and western folklore. Ceiling beams, light fixtures, handrails and other building elements were decorated to reflect the popular attractions of New Mexico's native peoples and natural wonders. Well-known local artist Carl von Hassler created murals for the lobby area, depicting the mythical Seven Cities of Cibola.

The KiMo was purchased by the City of Albuquerque in 1977 for use as a community arts center. Following plans by architects Harvey Hoshour and Dan Pearson, the theatre's exotic details have been carefully restored and updated to serve a new generation of New Mexicans. As a Landmark, even the shape and proportion of the marquee as well as the colors used in the 1982 renovation must be preserved.

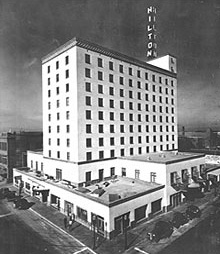

La Posada de Albuquerque

125 Second NW, 1939, Anton Korn

La Posada (the old Hilton Hotel) was built by hotel magnate Conrad Hilton in 1939. Hilton, a native of San Antonio, New Mexico, and already the owner of several Texas hotels, made the Hilton his first construction project after the worst of the Depression. It represented the culmination of a lifelong desire to succeed in Albuquerque and an affirmation that the city would become a major business center.

The hotel was and is a remarkable blend of old and new. It was the first modern high-rise hotel in the state; its mechanical systems were of the latest design. Because it's importance as a high-rise, the roofline can now not be changed. It was the only place in the city for quite some time after it was built to have a modern ballroom and meeting facilities. However, the brick coping along the roof, the interior design, carved woodwork, and most of the furnishings were rooted in New Mexican tradition and are among those features now protected.

The Hilton became the city's premier hotel. Among its guests were Zsa Zsa Gabor (while on her honeymoon with Conrad Hilton in 1941), James Stewart (stationed at the city's Kirtland Air Force Base during WWII), Lucille Ball, Lyndon Johnson and Spiro Agnew. Former governor Clyde Tingley became a regular in the lobby, meeting with the Democratic Party faithful.

In July 1945 Los Alamos scientists gathered in the hotel to await the results of he Trinity test of the atomic bomb. In June 1945 David Greenglass allegedly met Harry Gold at the Hilton to exchange atomic secrets. The hotel narrowly escaped being stripped of much of its southwestern interior in 1981. Its present renovation was completed in 1984.

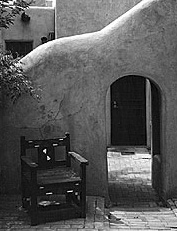

Las Mañanitas

1800 Rio Grande NW, Mid-19th Century, Architect Unknown

Las Mañanitas is a rare surviving mid-19th century adobe near the heart of the city. It has been remodeled over the years to accommodate its several owners, but evidence of its age is still readily apparent. The changes made by the many owners over the years are part of the reason it is a landmark. The varying roof heights, multiple patios, and rambling features of the house are extremely significant because they illustrate the history of the house through its owners.

Current residents of Duranes, the old farming community surrounding Las Mañanitas, remember their grandparents recalling that the building was a stagecoach stop on the road through the valley to Santa Fe, El Camino Real (including sections of Rio Grande Boulevard).

It also operated as a pool hall and a bar and there are tales of exuberant dances or bailes held in the large living room or sala. The Speronelli family owned the house and land at the turn of the century; they had a blacksmith shop and iron artifacts from the shop have been found on the property. Later owners added rooms, which were eventually joined together into a harmonious whole.

Despite changes to the house, many architectural features remain from its early days. A thick dirt roof lies beneath the standard tar and gravel roofing. The massive walls are made from terrones, sod blocks cut from marshes along the river. The depth of the walls is clearly seen in the low-set windows (some only a foot or so from the ground) with their deep reveals. Within the building, original round hand-adzed vigas (roof beams) support the sala roof, and corner fireplaces warm several of the rooms.

Main Public Library

501 Copper Avenue NW

The Main Public Library of the City of Albuquerque was designed by George Pearl of Stevens, Mallory, Pearl, and Campbell (SMPC) Architects and completed in 1975. In Downtown Albuquerque, the library was part of the 1968 Tijeras Urban Renewal Program (TURP). George Pearl designed the building, embracing a modern and simplified Brutalist style, and the library is one of the few examples of Brutalist architecture in New Mexico.

The library is a three-story structure, with two levels above ground and one below street level. Constructed primarily of brick and concrete column and slab elements, the building features a concrete plaza encompassing its perimeter. An angled concrete sign, bearing a common Brutalist chiseling pattern, marks its presence at the intersection of Copper Avenue and 5th Street.

The library showcases sand-colored brick walls and the street-level floor, accessible through the main entrance, comprises a central rectangular area surrounded by rooms utilized for study and offices. The design incorporates flexibility, enabling easy adaptation to evolving library needs. A 9-ft square grid system on the ceiling facilitates modifications to the main rectangular spaces on all three levels.

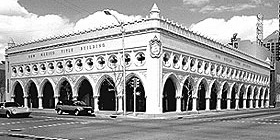

Occidental Life Insurance Building

305 Gold SW, 1917, Henry C. Trost

Unique in the country (a similar building in Oklahoma City was demolished in 1972), the Occidental Life Building ranks with San Felipe de Neri Church and the KiMo Theatre as one of Albuquerque's best-known and best-loved monuments. The origin of its design is reputedly a suggestion prompted by a European tour by Occidental president A.B. McMillan. His architect, Henry C. Trost of El Paso, modeled the 1917 building on the Doge's Palace in Venice. It was one of the last works Trost designed.

Trost designed the building to have an overhanging cornice; the interior was finished in mahogany and Circassian walnut and there were nine-foot deep porches on the south and east. A fire in April 1933 destroyed the roof and interior. The 1934 rebuilding, designed by Albuquerque architect Miles Britelle, made the roof edge more closely resemble that on the original Doge's Palace and the office space was built out, removing the deep open arcade.

The building is sheathed in glazed white terra-cotta tile manufactured by the Denver Terra-Cotta Tile Company, the supplier for both the original construction and the rebuilding. Pointed Venetian Gothic arches range down the street façades capped by a row of quatrefoils; much of the tile is formed into interlocking floralpatterns. In 1981 a two-story office building was built within the original walls. Because of the changes to the interior, the terra cotta façade is the most important feature that must be preserved.

Old Airport Terminal

2920 Yale SE, 1939, Ernest Blumenthal

The Old Airport Terminal serves as a reminder of two very important pieces of Albuquerque's history - the growth of the aviation industry and New Deal public works programs. Opened in 1939, the Old Terminal served as a link for trans-continental flights until 1965, when a new terminal was constructed just to the east. It was the first commercial passenger terminal in the state, and is one of the few remaining historic transportation facilities left in the city.

The Municipal Airport began with the sale of land to the city by Transcontinental and Western Airlines in 1936. Designed by then City Architect Ernest Blumenthal, construction for the terminal began on the site in 1937, completed in 1939. Funded by the Works Progress Administration, construction utilized local materials, including adobe bricks made on the site and wood and flagstone from the mountain forests near the city.

WPA workers spent thousands of hours crafting details of the building. Exterior features include a stepped parapet, exposed vigas, wooden posts with corbel brackets, and observation tower and a flagstone entry. The main lobby area is of the most historical significance on the interior of the building, featuring high ceilings with herringbone latillas, rough-hewn beams, heavy wood columns with corbel brackets, rough-plastered walls, recessed bays with ornate wooden screens, tin chandeliers, flagstone floors, and a corner fireplace. During WWII, the U.S. Government occupied and operated out of the terminal, which led to the establishment of the Albuquerque Army Air Field, and eventually Kirtland Air Force Base.

The original 1939 building has been altered with several later additions, but the early form and integrity of the structure, including the interior detailing, remains essentially intact. The Junior League of Albuquerque, with offices in the building at the time, pursued a National Register of Historic Places designation for the Old Terminal in 1989.

Since then, work has been done to rehabilitate and restore the Old Airport Terminal. The first phase of rehabilitation was implemented in 1997 that included the demolition of all the additions post-1945 and basic renovation to the 1942 and 1945 buildings to bring the terminal up to code and restore among other things the casement windows and lighting. The second phase began in 2001 and includes site revisions to the traffic island and walkways and contemporary rehabilitation of the original Ticket Counter into a reception counter.

The Sunport’s Old Terminal is available for rent. Please contact Doug Lutz for more information.

Old Albuquerque High School

Central/Broadway NE; 1914, 1927, 1938-40; George Williamson, Louis Hesselden

Typical of school buildings of the period when most schools favored the brick and white trim typical of the Gothic Revival style, Old Albuquerque High served as the city's only high school from 1914 to 1948. The complex continued as a school until the 1970s when it was sold to a private developer. There have been many plans for its renovation; so far none has succeeded.

Five buildings around a central courtyard form a compact campus. The original building is, of course, Old Main (1914), which faces Central Avenue. Designed by El Paso architect Henry C. Trost, who designed many of the city's premier buildings. It included a science laboratory, gymnasium (complete with bleachers), library, and 850-seat auditorium, as well as classrooms. With these facilities it provided quality education to as many as 500 students yearly. At the time critics considered the building too large. In 1927 local architect Gorge Williamson was commissioned to design a Manual Arts Building in a similar style north of Old Main on Arno. It included a woodshop, classrooms, and a lunchroom.

Ten years later, Albuquerque Public Schools took advantage of New Deal funding and WPA manpower to add still three more buildings to the complex: the Classroom Building (1937), the large Gymnasium Building (1938), and the Library Building (1940). All three were designed by another local architect, Louis Hesselden, to blend with the established Gothic Revival style of the first two buildings.

Over the years, projects to adapt and reuse the school for various commercial and housing purposes were unable to get off the ground until recently. The Lofts, the redevelopment project currently renovating Old Main and the Classroom Building, will be reusing the classroom space as apartments. As a Landmark, the interior spaces are also protected, and the main library room and gymnasium spaces are preserved as such.

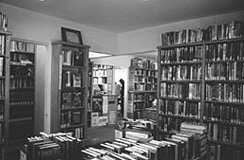

Old Main Library

423 Central NE, 1925, Arthur Rossiter

The original portion of the Old Main Library was constructed in 1925 on a parcel of land donated to the city in 1900 by Joshua and Sarah Raynolds. The library was designed by Arthur Rossiter and includes interior decorations by prominent Santa Fe artist Gustav Baumann. The 1890 brick school building on the property (the first Albuquerque Academy) served as the city library from 1901 to 1924. Additions, including Botts Hall at the front of the early building, were completed in 1947 and 1951, but much of the original form and detailing—both interior and exterior—are still apparent. Local architect Gordon Ferguson designed the additions.

The building is an excellent example of Spanish-Pueblo Revival architecture. The parapet, central bell tower, corner buttress towers, protruding beams, and entryway with exposed beams and corbel brackets are design features consistent with this important regional style. The original Prairie-style windows are relatively rare in Albuquerque.

Interior detailing includes heavy wooden columns and beams, and two corner fireplaces. Mr Baumann's decorations were restored in 1977, and can be seen in the main reading room along the walls and at the top of each post.

Old Main was renamed the Special Collections Library when the new main library was opened downtown in 1975. It houses major research collections in genealogy and New Mexico history, as well as a museum of the history of books and printing, the Center for the Book. It is open to the public during posted hours.

Roosevelt Park

Coal/Spruce/Sycamore SE, 1933, C. Edmund "Bud" Hollied

Roosevelt Park opened during the middle of the Great Depression. It was built with federal Civil Works Administration funding obtained through Albuquerque Mayor Clyde Tingley's close friendship with President Franklin Roosevelt. The park's name was changed from the original "Terrace Park" soon after its opening to honor its popular benefactor. Designed by local landscape architect and greenhouse operator C. Edmund "Bud" Hollied, the park remains one of the Southwest's best examples of New Deal landscaping.

Hollied envisioned a sprawling, lush park in what was previously a sandy, garbage-strewn arroyo. With the work of 275 CWA laborers, each paid $39 per month, the park took form between the winter of 1933 and summer of 1934. It cost $122,338 to transform the 13-acre site. Over 2,250 trees and bushes, including umbrella catalpas and Tingley's beloved Siberian elms, were planted. An abutment along the south side of the park was built with stone from the demolished county jail at Rio Grande and Central. Its landmark status protects all of these features, even including the elms.

The general layout and landscaping scheme of the park remain essentially unchanged over the last 60 years.

When the park was completed in 1935 it had a driveway that encircled it; it has since been blocked so that only maintenance vehicles can use it now. Roosevelt Park continues to be a popular location for recreation and relaxation in the heart of the city.

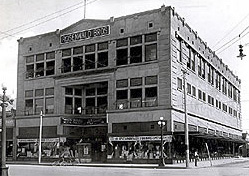

Rosenwald Building

320 Central SW, 1910, Henry C. Trost

The Rosenwald Building was opened in 1910 to great acclaim. The Albuquerque Morning Journal rejoiced: "With the opening of the Rosenwald Brothers store, at the corner of Fourth Street and Central Avenue, yesterday afternoon, Albuquerque gained the distinction of having within its boundaries the handsomest, most up-to-date, and most complete department store in the southwest."

For its time, the Rosenwald was as modern as they came. It was the city's earliest reinforced concrete structure and probably the first fireproof building in New Mexico. Its massiveness, two-story entrance bay and minimal decoration reflect the Chicago training of its architect, Henry C. Trost.

Brothers Aron and Edward Rosenwald were German merchants who came to Albuquerque in 1878 to open a store in Old Town. Soon after 1880, when the railroad created a new town a mile and a half east of the old Spanish villa, they moved their store "downtown." Their children continued and expanded the enterprise and in 1908 commissioned Trost, probably the best-respected architect in the southwest, to design a premier store building.

Originally the entire building was used as a department store until a fire in 1921 necessitating a six-year total renovation. The building remained a major department store until 1927 when the ground floor was then leased to McLellan Stores, which remained there for 50 years. It was renovated in 1981 and now houses offices.

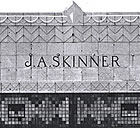

Skinner Building

722 Central SW, 1931, A. W. Boehning

This fanciful building began life as a grocery store! In 1931 A.J. Skinner asked local architect A.W. Boehning to design what was to become the flagship store of his local chain of food stores. The result was this gleaming "jewel box" structure.

The Skinner Building is most notable for its Art Deco style ornamentation. A close look reveals a wealth of small details. The terra-cotta tile, which covers the underlying brick, has been molded into a variety of geometric designs: swags, zigzags, leaf shapes, chevrons, and fluting. Unlike most Art Deco buildings, which are so tall that the decorative elements are hard to see, the Skinner Building offers a close look at its decoration. Albuquerque has few examples of Art Deco, so the Skinner Building is treasured for its rarity and the craftsmanship and imagination evident in its design and construction. Unlike the KiMo's incorporation of southwestern detailing, the Skinner building opted for a more conventional art deco style. In addition, the building is of brick construction and there is a tin ceiling inside much more typical of East Coast and Midwest buildings of the time.

A grocery store operated in the entire building for ten years and then it was leased to various firms, including the Pepsi Cola Company, which used it as their local headquarters. The Skinner family sold the property in 1970and in 1977 the City purchased it as part of a downtown revitalization project. The City later sold the building to the present owner with stipulations that the street façades and overall Art Deco detailing be preserved.

Since then, the owner has constructed a second floor balcony that wraps around the street façade. It is of steel and glass construction with many different colored lights illuminating the street and architecture. It is not attached to the building itself, but stands one inch from the building.

Sunshine Building

120 Central SW, 1924, Henry C. Trost

The Sunshine Building was one of Albuquerque's first "skyscrapers" and its first great cinematic palace, with an elaborate 920-seat theater. Its "main street" appearance, stores and theater entrance at the street with solid commercial building above, reflects an era when local developers were anxious to make Albuquerque and all-American town, the equal of any on either coast or in the Midwest.

The man behind the Sunshine was Joseph Barnett who came to Albuquerque in 1883 from New York City with his family. The young Barnett went into real estate and became a prominent entertainment entrepreneur, once owning all the city's theaters. The Sunshine opened with much fanfare on May 1, 1924. Its first movie was "Scaramouche" starring Ramon Navarro; the showing included a special orchestra to accompany the film. The theater continued to screen films until the 1980s, undergoing a major interior remodeling in the 1960s to allow installation of a large screen. It was remodeled again in the 1990s to facilitate presentation of live music performances.

Henry C. Trost, the predominant architect in Texas, Arizona and New Mexico for the first three decades of this century, designed the building. He had pioneered the use of reinforced concrete in the Southwest and it is used here covered with variegated yellow brick. The restored marble and oak lobby boasts a rare remnant of the building's early days, an attendant-operated elevator, which is now the only one left in the state. The façade and lobby are both protected now that it is a landmark.

The Whittlesey House

201 Highland Park Circle SE, 1903, Charles Whittlesey

Who would expect to find a Norwegian log cabin in the heart of the Southwest? Yet here one is and has been since 1903, when its owner/architect Charles Whittlesey built it for his family. One of his daughters remembered "the big log house on the edge of the mesa" and its large living room "with an immense fireplace with log stumps on the hearth where we used to crack nuts..." She recalled a 10-foot veranda surrounding the living room on three sides: "It was all very beautiful with a marvelous view."

Whittlesey is best known as the architect of the city's famed and much-mourned Alvarado Hotel. He was also known as a pioneer in the use of reinforced concrete. His home on the mesa edge is similar in materials and design to another Santa Fe Railway hotel, El Tovar at the Grand Canyon. El Tovar was designed by Whittlesey in the same year he built this house. The buildings share log-cut walls, Norwegian style cutout railings edging wide verandas and recessed window seats.

The house is also closely identified with Clifford Hall MacCallum, a nurse who had come West with a convalescing T.B. patient and stayed on to become head nurse at the Sanitarium. The story goes she informed a suitor that if he bought the house for her she would marry him, which he did in 1920. She lived here for 40 years, often remodeling the interior and carefully maintaining it so that the house became a local showplace, a gathering spot for artists and writers. In 1960 it was sold to a fraternity and was later used as a home for indigent men. The Albuquerque Press Club bought the property in 1973 and operates it as a professional and social club.

A fire in 1974, due to the wiring, destroyed the old bar and kitchen wing on the southwest corner of the building. Since then a long range plan for improvements to the building was made to help preserve the building from further damage.