Cartoon Formalism

Cartoon Formalism

Works on Paper in the Permanent Collection

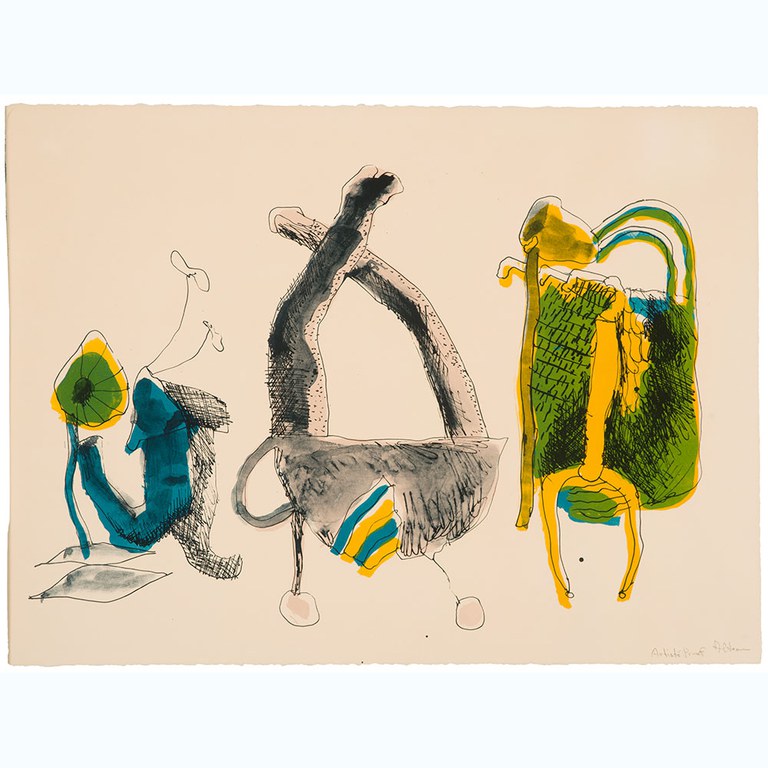

John Altoon, Tamarind #1, 1965, lithograph, Albuquerque Museum, gift of Jeri Coates

Carol Summers, Burning Mountain (#88/100), date unknown, color lithograph, Albuquerque Museum, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Richard Cronin

Cartoon Formalism is on view in Albuquerque Museum's Angelique + Jim Lowry Gallery for Works on Paper.

Details subject to change.

Cartoon Formalism featured Funk Art from Albuquerque Museum’s art collection. The term “funk” is borrowed from New Orleans Jazz of the 1920’s known for its soulful blues—simultaneously happy and sad in a single song.

For much of the twentieth century, the tension between figuration and abstraction was the defining conflict in how art was made, thought about, and presented. Figurative art describes any form of modern or contemporary art that references the natural world and particularly the human body. Many major art movements and artists abandoned this type of art and instead adopted a formalist approach exploring the world of abstraction though color, line, and shape. The context of the work was de-emphasized or completely removed suggesting that the value of a work is based purely on what it looks like rather than the stories it might tell or feelings it might express.

Funk Art is the exact opposite—not officially considered a movement, “funk” is an intensely personal process, contrasting the characteristics of the light-hearted cartoon with intense and serious topics. The artists featured in this exhibition pushed back against the ideals of formalism and redefined how the body and the natural world could be dynamic and expressive elements of their work that was primarily produced between the 1960s and 1980s. The Funk aesthetic found its roots in Northern California amongst Bay Area figurative painters like Joan Brown and Richard Diebenkorn, and in Los Angeles with John Altoon and Andy Warhol. Moving away from the kind of abstraction that triumphed in New York at the time, these artists created work that is ironic and playful in appearance, while presenting serious psychological and personal subjects.

While the subject matter of the works in this exhibition varied from pets to social satire, each work conveyed something intimate. Some of the artworks, like Fritz Scholder’s lithograph Happy Skies to You, referenced the body directly, others, like John Altoon’s lithograph Tamarind #1, blurred the lines between the figurative and the abstract essentially dismantling the attitude that one approach or the other was superior. These artists often created works that were vibrant, sensuous, and quirky as they demonstrated how artists were breaking the rules dictated by the ideas of formalism.

Funk Art is an attitude.

Funk Art is a social counter-culture movement.

Funk Art is anti-aesthetic.

Examples of how artists were experimenting with different visual languages and art forms from this time period can be seen in other exhibitions at Albuquerque Museum including Let the Sunshine In and Dreams Unreal: The Genesis of the Psychedelic Rock Poster.

ARTISTS ON VIEW: Walter Askin, John Altoon, Walter Askin, Joan Brown, Robert Colescott, Roy De Forest, Richard Diebenkorn, George McNeil, Fritz Scholder, Sam Scott, Carol Summers, Andy Warhol, and William T. Wiley.