Unfolding Tradition

March 23–January 19, 2020. Works on paper by Japanese artists in the collection.

Unfolding Tradition

Works on Paper by Japanese Artists in the Collection

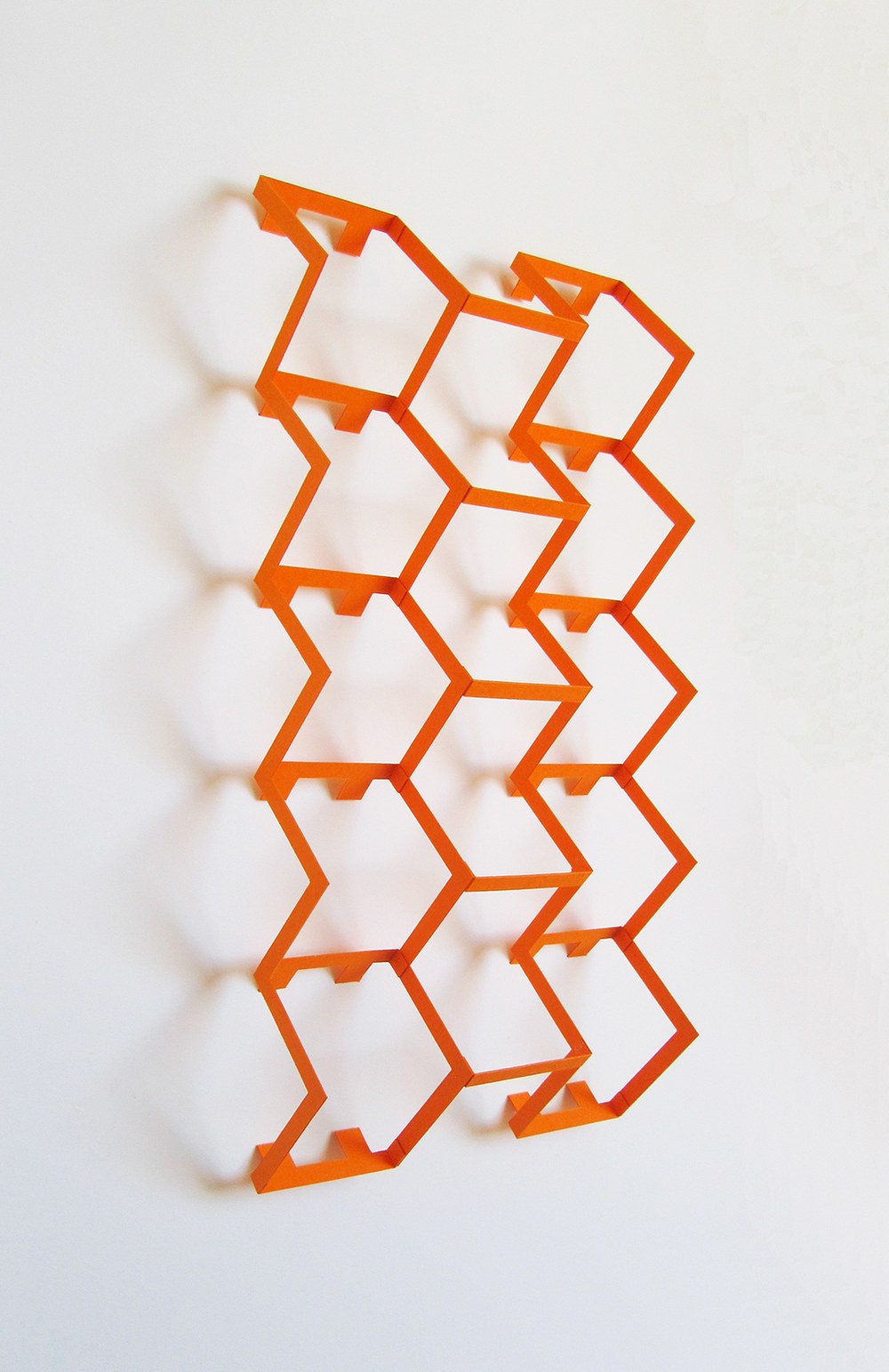

Emi Ozawa, (born 1962 Tokyo, Japan; lives Albuquerque, New Mexico), Big Orange Bite, 2018, paper on board, unique variation edition, promised gift of Richard Levy and Dana Asbury, image courtesy of Richard Levy Gallery

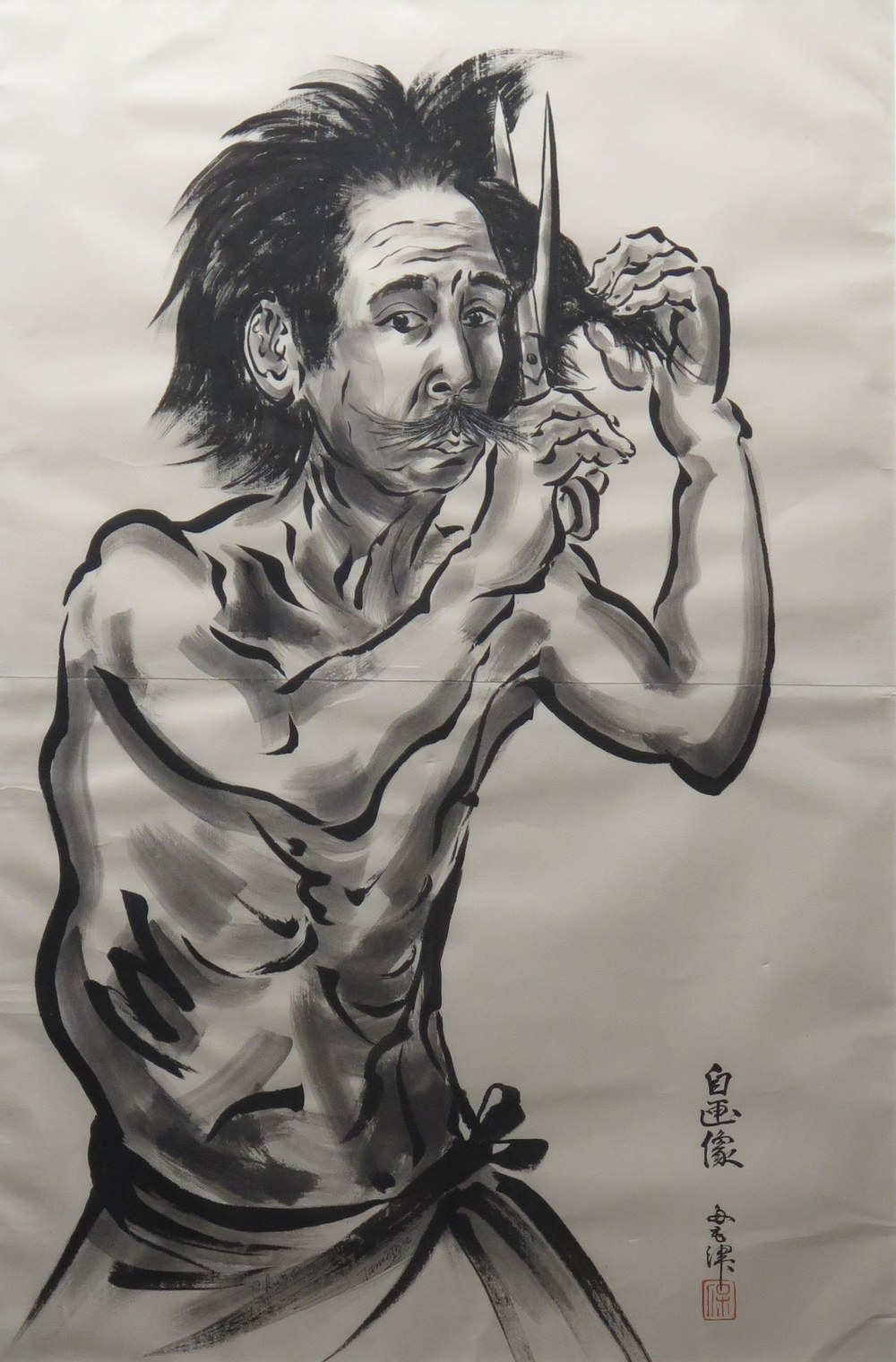

Chuzo Tamotzu (1888 Amami Oshima Island, Japan–1975 Santa Fe, New Mexico), Self Portrait Cutting Hair, 1963, Sumi ink on paper, gift of Louise Tamotzu

Nature and the human form have long been important subjects in Japanese art. Unfolding Tradition features 19th-century woodblock prints from the Edo period alongside contemporary works through which artists both engage with and redefine traditional Japanese subjects, techniques, and approaches to making art. The contemporary artists reflect on the aesthetics, history, and society of Japan but they also represent the meeting of East and West and some venture into making new more abstract forms of art.

Before Buddhism was introduced from China in the 6th century, Shinto was the faith of the Japanese people. In the Shinto belief system, Kami, or deities, are believed to exist in nature, so an image of a landscape is often referencing the gods who exist within the natural features. In Utagawa Hiroshige’s Women Pilgrims At Enoshima at the Opening of the Festival of Benten, for example, water is one of the seven gods of luck.

The Edo era (1615–1868) in Japan was a period of stability and prosperity. The sale and production of woodblock prints, ukiyo-e, expanded greatly. Ukiyo-e means pictures of the floating world. In the context of Edo, these woodblock prints highlighted urban lifestyle, fashion, and entertainment. Works by Keisei Eisen and Utagawa Toyokuni feature everyday life as well and the luxury of the upper classes during the time period.

Contemporary work by Kei Tsuzuki examines the connections between the natural world and the spiritual world through animal figures. Chuzo Tamotzu looks inward in his intimate Self Portrait Cutting Hair but also outward in his watercolor Sandias, which features New Mexican farmers. Though this local landscape is visually similar to a traditional Japanese landscape painting, the people and place are distinctly Albuquerque.

Masami Teraoka and Patrick Nagatani bring the human form together with food to draw attention to social issues such as the impact of the West and consumerism on Japan. In each of their works, the hamburger becomes a metaphor for the ways in which culture and tradition are being threatened.

Emi Ozawa departs from subjects of the natural world and the human form constructing geometric designs that are playful. Her painted wood wall sculptures explore color, line, and shadow. For each of the larger sculptures, she created an elaborate model with paper. Big Orange Bite is an example of the intricate process, precision, and craftsmanship that defines Ozawa’s studio practice.

The wide-ranging selection of art in this exhibit was drawn from the Albuquerque Museum’s permanent collection of works on paper, and includes artists who lived solely in Japan, immigrants to the US, and natural-born American citizens of Japanese ancestry.

Unfolding Tradition was on view in Albuquerque Museum's Angelique + Jim Lowry Gallery for Works on Paper.