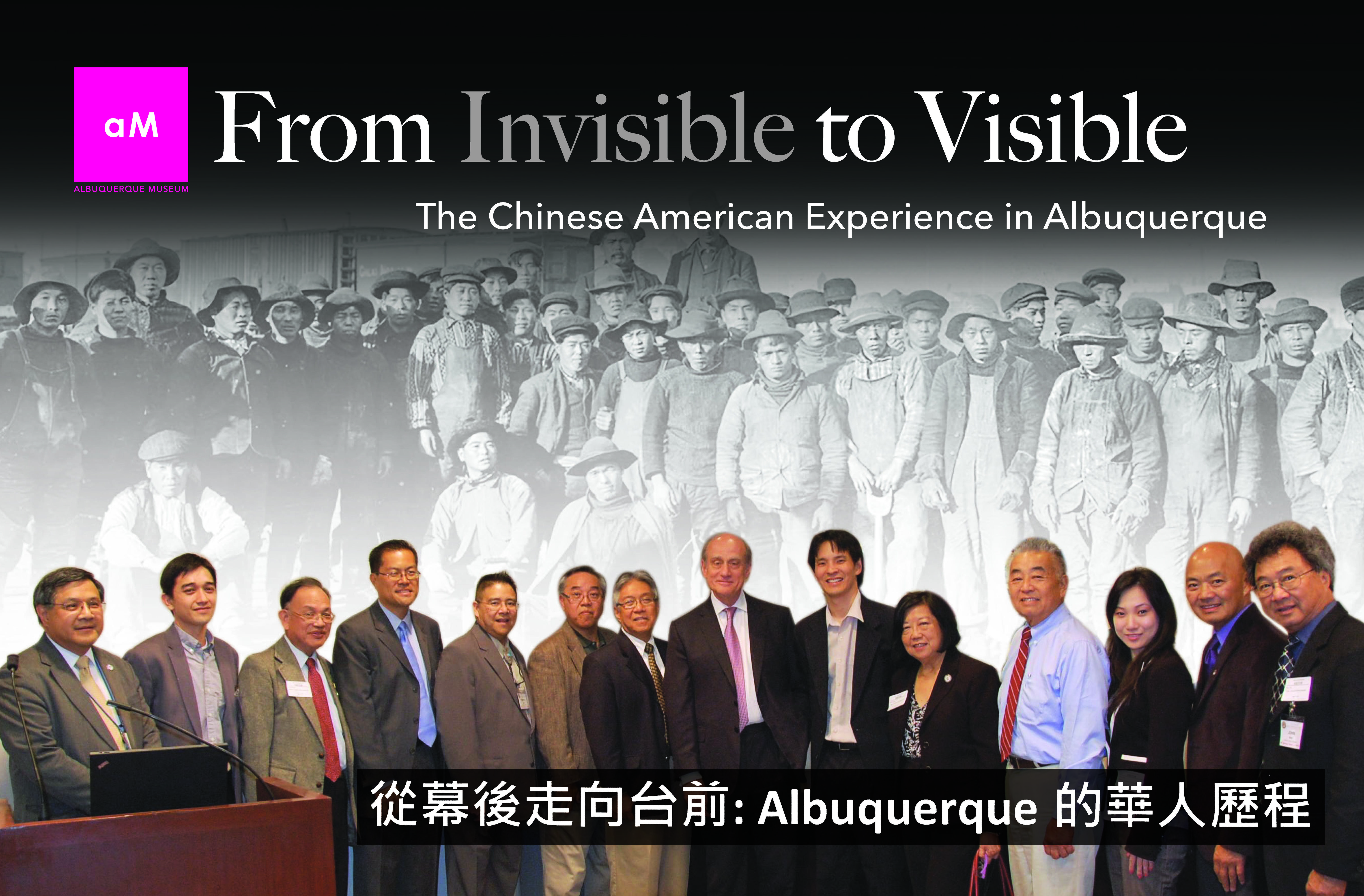

From Invisible to Visible: The Chinese-American Experience in Albuquerque

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Committee members:

Siu Wong, Chair, Chinese American Citizens Alliance – Albuquerque Lodge

Carolyn Chan, Chinese American Citizens Alliance – Albuquerque Lodge

Rusty Chan, Chinese American Citizens Alliance – Albuquerque Lodge

Yung Sung Cheng, Chinese Institute of Engineers- New Mexico

David Phillips, University of New Mexico Maxwell Museum

Yu-Lin Shen, New Mexico Chinese Association

Lin Ye, Albuquerque Sister Cities Foundation

Donors: Carolyn and Tony Chan, Ed Jeung, Panda Express Restaurant, Talin Market, PNM – Public Service of New Mexico

Sponsors: Chinese American Citizens Alliance, Chinese Institute of Engineers- New Mexico, New Mexico Chinese Association, Albuquerque Sisters Cities Foundation and the University of New Mexico Maxwell Museum, Kim Jew, Shane Flores, Moji Cinema

Narrator on Videos: Rusty Chan

Chinese immigrants first arrived in New Mexico when it was part of the Spanish Empire. Immigration began in earnest during the U.S. Territorial Period, after the California Gold Rush of 1849. Arriving on the West Coast, Chinese men worked in mines and on railroads, as farmers, as laundry and store owners, and as servants—anything that would allow them to support their families in China. As railroads spread east from California, Chinese immigrants provided most of the labor to build them and followed the new railroads into the Rocky Mountain West. In the 1880s, Albuquerque’s railroad-driven population boom included Chinese-born residents.

Newspapers and political leaders demonized the new immigrants as a “Yellow Peril,” and Congress and the states passed laws to prevent the Chinese from settling in the U.S. permanently. Federal laws also prohibited Chinese family members from joining working men, so these men had to leave their wives and children in China. Nevertheless, a Chinese immigrant community took root, and its members slowly built new lives in America.

Chinese immigrants sought a better life for themselves and their families, but like other immigrants, they endured violence and legalized discrimination. They struggled for civil rights that others took for granted. By the early 1900s, Albuquerque’s first Chinese American community had been driven out of existence, but new arrivals re-established the community. Today, about 1 of every 230 Albuquerque residents is of Chinese ancestry.

The Chinese Americans of Albuquerque are often overlooked. This exhibit honored the way they embraced their new country, overcame anti-Chinese bias, and contributed to the legal, educational, social, and economic fabric of the city, the state, and the nation.

MAKING A LIVING

Beginning in the mid-1800s, large numbers of men from Guangdong Province migrated to Gum Saan (“Gold Mountain,” meaning California). They needed the income to support families suffering from famine and economic upheavals. These men took whatever jobs could be found, doing work that most Americans avoided. Many became railroad workers, migrating eastward into Rocky Mountain states including New Mexico.

Rapidly growing towns along the railroads—such as Albuquerque, Las Vegas, and Deming—provided economic openings for the newly arrived Chinese. They became truck farmers or opened small businesses such as laundries, general stores, and restaurants. One of Albuquerque’s first Chinese store keepers was Sam Kee, who specialized in Chinese and Japanese goods. At first, Mr. Kee’s broken English was a source of patronizing amusement among “Anglos,” but his son graduated from Albuquerque High School as class valedictorian and went to college. In 1918, Edward Gaw founded Fremont’s Fine Foods grocery store, which gained local fame for its gourmet foods and remained in operation until 2012. During the Great Depression, the Wing Ong family operated grocery stores in the Barelas area; later they helped run the Chung King Cafe downtown, and after World War II they founded the popular New Chinatown Restaurant.

Fifteen percent of Chinese American males served in the armed forces during World War II. The GI Bill enabled those veterans to obtain college degrees upon return. At the same time, legalized discrimination against Chinese Americans began to crumble. The Chinese American community was quick to take advantage of their expanding professional opportunities. Today, Chinese Americans commonly serve in the scientific, engineering, medical, and other professional fields.

EDUCATION

Since ancient times, Chinese culture has stressed the value of education. Chinese immigrants came to America to make a living, but they also sought ways to better educate their children (and often themselves). Given this commitment, it’s not surprising to learn that in 1906, Sam Ho Kee was Albuquerque High School’s valedictorian. Today, educational achievement still remains an important Chinese cultural value, as illustrated by the stereotype of the “Tiger Mother”. The term was coined by law professor Amy Chua to describe a traditional Chinese parent who encourages her children to high levels of success in life and academics.

Recent Chinese immigrants have arrived not only from mainland China but also from Taiwan, the Philippines and other Southeast Asian countries, and other parts of the world. Some came with minimum education and skills, but others were highly trained. Data from 2015 show that 54 percent of Chinese Americans aged 25 or older have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 30 percent of Americans in general. Albuquerque’s relatively few Chinese Americans play an important role in the local economy, in part because of their strong commitment to education.

CIVIL RIGHTS

Chinese immigrants faced claims that they took American jobs, which led to Congress passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a law designed to keep Chinese people out of the country. In New Mexico, the state constitution was amended in 1921 to prevent Asians from owning real property; this amendment was not expunged until 2006. In some parts of Albuquerque, property covenants stipulated that Chinese Americans and African Americans could live in homes only if they were employed there as domestic workers.

In response to legalized hostility, Chinese Americans became pioneers in civil rights and used the legal system to protect their Constitutional rights. The Chinese American Citizens Alliance (C.A.C.A.), founded in San Francisco in 1895, is the oldest Asian American civil rights organization in the U.S. One outcome of their civil rights struggle was the Magnuson Act of 1943, which repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The C.A.C.A. Albuquerque Lodge was founded in 1961. In 2011 and 2012, it helped obtain passage of Senate Resolution 201 and House Resolution 683, expressing Congress’ regret for passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

COMMUNITY

Albuquerque’s Chinese Americans have established multiple organizations that celebrate their members’ Chinese heritage while involving them in American society.

The Albuquerque Lodge of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance, founded in 1961, supports the alliance’s mission of civil rights, good citizenship, youth development, American patriotism, and historical and cultural preservation. Lodge members Carolyn, Tony, and Rusty Chan and Siu Wong have served on the C.A.C.A.’s national board, and Carolyn Chan served as national president. Dr. David Hsi, Carolyn Chan, and Dr. Tony Chan have received the Spirit of America Award, the C.A.C.A.’s most prestigious national award.

The New Mexico Chinese School of Arts and Language was founded in 1978 and this year is celebrating its 40th anniversary. The school has helped teach more than 1,800 Albuquerque residents to speak, read, and write Chinese and to appreciate specific aspects of Chinese culture.

Other community organizations include the New Mexico Chinese Association, the Albuquerque Chinese Chorus, the New Mexico Chapter of the Chinese Institute of Engineering—USA, the Chinese Culture Center, and the Asian American Association of New Mexico. Through these organizations, Chinese Americans participate in traditional festivals such as the Chinese New Year and the Moon Festival, and in public events such as the Festival of Asian Cultures.

New Mexico’s Chinese Americans also give their time and money to community-wide organizations such as the Albuquerque Museum, Explora, the New Mexico Museum of Natural History, Lions and Rotary clubs, educational institutions, and charities such as Goodwill.

A GROWING PRESENCE

For more than three decades, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 kept most Chinese out of the U.S. but did allow immigration by a few skilled individuals such as diplomats, merchants, and students. In 1915 a court ruled that Chinese restaurant workers fell under the skilled worker exception to the law. The predictable result was a rapid growth in Chinese restaurants, which enterprising individuals used to obtain visas for family members.

During World War II, China was a U.S. ally and thousands of Chinese Americans served in the armed forces—forcing the country to rethink its anti-Chinese attitudes. In 1943 the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed. In 1946, under the War Brides Act, it became legal for Chinese American GIs to bring Chinese wives into the country. After the war, many Chinese arrived as university students, especially in the fields of science and engineering. During the Cold War, most Chinese students came from Taiwan, but in 1978, mainland China began sending students to the U.S. In 2016, three out of every ten foreign students in the U.S. were Chinese, making them the largest contingent of foreign students.

Often, Chinese American students choose to stay and raise families. Many work at Sandia National Laboratories, Los Alamos National Laboratory, the University of New Mexico, and other research organizations.

Legalized discrimination is a thing of the past, and today’s Chinese Americans can focus on making a living, improving their children’s lives, and contributing to American society. However, they have not forgotten the past. The success of Albuquerque’s Chinese American community required a long uphill struggle and is an inspirational lesson for all.