Fashion in 1950s Albuquerque

Everybody loves to dress up. Like a second skin that can be changed at will, clothing is a vehicle for metamorphosis, a way to convey who we are at any given time. Through fashion, we express ourselves – sometimes, in not so subtle ways – to those around us. We also express ourselves within the larger context of, and in response to, the events that shape our lives.

Everybody loves to dress up. Like a second skin that can be changed at will, clothing is a vehicle for metamorphosis, a way to convey who we are at any given time. Through fashion, we express ourselves – sometimes, in not so subtle ways – to those around us. We also express ourselves within the larger context of, and in response to, the events that shape our lives.

Fabulous! presented a story of fashion trends in the Duke City after the debut of Parisian designer Christian Dior’s New Look in 1947, through the Museum's photograph archives and memorabilia from local shops and department stores. These fashions allow us to visualize our own “new look” – a distinctive regional expression with a hint of southwestern flavor that reflects the diversity of our community, but affirms that we have always been tuned in to national and regional trends.

Dior’s New Look

“It’s quite a revolution, dear Christian. Your dresses have such a new look. They’re quite wonderful, you know.” – Carmel Snow, February 12, 1947

As early as the mid-1940s, with America at war in Europe and Asia, European designers were playing with the concept of a New Look. In occupied France, the German-controlled fashion houses lacked the inspiration previously enjoyed – and often copied – by the industry. Working within the limits of the War Production Board’s garment restrictions, U.S. designers such as Claire McCardell and Gilbert Adrian focused on sportswear and ready-to-wear clothes with a fresh, yet functional “American Look.”

The end of World War II brought major changes to the industry. By 1946, Christian Dior was sketching ideas for fashions that reintroduced the concepts of femininity and luxury in clothing. His collection was presented for the world to see in the February 1947 issue of Vogue magazine, complete with articles describing the features of his designs. Spreading quickly through the Allied nations, yet fraught with controversy, the New Look was immediately adopted by American designers and their eager clients.

New Shapes

“A dress is a piece of ephemeral architecture, designed to enhance the proportions of the female body.” – Christian Dior, 1947

“Was he mad, this man? Was he making fun of women? How, dressed in “that thing,” could they come and go, live or anything?” – Coco Chanel

The basic concept of the New Look mirrored in many ways the concepts behind designs for architecture, sculpture and decorative arts of the late 1940s and 1950s. Essentially, the function of an object could be enhanced by a more adventurous expression of form, making it more visually satisfying.

Architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Aero Saarinen used curves and arches to express the creative potential of pure line. The mobiles of Alexander Calder, with their moving, changing shapes, were especially popular. In their designs for functional yet modern furniture and appliances, Charles Eames, George Nelson and others took advantage of unusual materials to emphasize shape and line including curves, tapered forms and hourglass shapes. These shapes are similarly reflected in metal work, glass, and ceramics produced during the period.

Christian Dior’s New Look translated these trends into clothing that enhanced the inherent beauty of the female body. Shoulder lines became more natural and rounded, bust lines were emphasized, waistlines were minimized, and hips were exaggerated to create “tulip” and “teacup” curves, completing the look. Hemlines were also drastically dropped, and numerous yards of extra material – considered by many to be outrageous after the severity of earlier restrictions – were added to maximize the effect.

New Patterns

Trends in the art world also provided fuel for igniting changes in the appearance of fabrics. Fabric designers looked to the work of painters such as Jackson Pollock, Joan Miró and Salvador Dalí for inspiration to create colorful, expressive patterns used in clothing, as well as upholstery fabric, draperies, area rugs, and wallpaper.

Patterns ranged from totally abstract compositions to bold, repeating designs organized around stylized images of familiar objects. At the same time, fabric manufacturers experimented with the composition of the materials themselves, creating clothing that was easier to care for, wrinkled less, and would last – at least until the next fashion season.

Patterns ranged from totally abstract compositions to bold, repeating designs organized around stylized images of familiar objects. At the same time, fabric manufacturers experimented with the composition of the materials themselves, creating clothing that was easier to care for, wrinkled less, and would last – at least until the next fashion season.

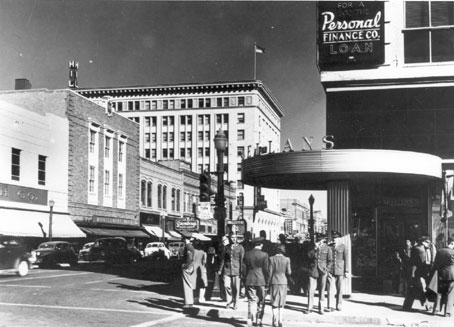

New York City and Los Angeles became the design centers for America’s interpretation of the New Look. Designers created versions that were affordable to the general public, and then distributed them throughout the country’s best shops and department stores. These fashions made their way into Albuquerque’s retail district, and to find them, you had to go…Downtown!

Use it up, Wear it Out, Make it Do

In 1940 the City of Albuquerque held the Coronado Quarto Centennial, which commemorated four hundred years of cultural diversity in the Albuquerque area. The celebration was an opportunity for the city to market itself as a unique tourist destination after the Depression years.

With the bombing of Pearl Harbor only one year later, America plunged into World War II and Albuquerque played a significant role in the effort to win. At Kirtland Army Air Field, crews were trained as pilots, bombardiers, and mechanics for the B-17, B-24 and B-29 bombers. At Sandia Base, engineers designed and tested bombs that would bring a lasting, but horrible, close to the war in the Pacific. Albuquerque’s enlisted and civilian families, working for the war effort and with precious little time to shop, spent their paychecks downtown. After the liberation of Europe in 1945, soldiers were given thirty days after discharge to get out of uniform and back into civilian clothes.

Before the New Look arrived, wartime fashions were loosely based on the look of military uniforms, and featured minimum yardage and few embellishments. Working women dressed for comfort. Boxy, padded shoulders and knee-length hems were the standard; turned up cuffs and patch pockets were banned. Silk stockings were scarce, so women applied make-up to simulate the appearance of seamed stockings. With restrictions on leather, shoes were made from sensible materials such as reptile skins, fabric, wood, and cork.

Before the New Look arrived, wartime fashions were loosely based on the look of military uniforms, and featured minimum yardage and few embellishments. Working women dressed for comfort. Boxy, padded shoulders and knee-length hems were the standard; turned up cuffs and patch pockets were banned. Silk stockings were scarce, so women applied make-up to simulate the appearance of seamed stockings. With restrictions on leather, shoes were made from sensible materials such as reptile skins, fabric, wood, and cork.

Men’s fashions were also subject to wartime restrictions. Single-breasted suits with narrow lapels and shallow pleats, and cuffless pants were the accepted style. Boys lived in striped T shirts, jeans, and sneakers. Eventually a backlash prompted America’s first street style, the “zoot suit.” These colorful, hard-to-find outfits were baggy and deeply pleated in defiance of the War Production Board. Men seen wearing them were almost certainly looking for trouble!

Postwar Albuquerque

"Penney’s had everything, especially stockings. At first they had silk, and then they got the first nylons. They would wear forever; the kids said they were made like iron.” –Henrietta Loy

After the war, factories retooled for consumer production while designers from all over the world relocated to the United States. As newcomers from the East Coast migrated to Western cities, Albuquerque’s population steadily increased to over 95,000 potential shoppers by the end of the decade. In addition, the rerouted Route 66 and the Santa Fe Railway brought out-of-towners right into the heart of the city’s shopping district.

In response, the retail community expanded along Central Avenue. Shoppers dressed up to attend the Penney’s Grand Opening in 1949 which featured Jackie Barnes, winner of the Lux Girl contest, wearing a gown designed after the New Look.

In response, the retail community expanded along Central Avenue. Shoppers dressed up to attend the Penney’s Grand Opening in 1949 which featured Jackie Barnes, winner of the Lux Girl contest, wearing a gown designed after the New Look.

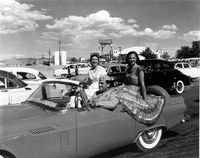

Men flocked to Stromberg’s for the latest business and formal fashions, or took their families out to see the latest automobiles at Jones Motor Company in Nob Hill. And, with University of New Mexico’s growing student population eager to graduate and generate an income, Albuquerque prepared as well as it could for the consumer explosion to follow.

The Shape of Speed

“My sense of proportion tells me that oblongs are more attractive than squares, just as a ranch house is more attractive than a square three-story flat-roofed house or a greyhound is more attractive than a bulldog.” – Harley Earl, GM Art and Color Division Head

"The cars we bought in the Fifties didn't look much like the cars in the showrooms. To the extent we could afford it, we customized our cars. Likewise, there was a self-modification of dress that was highly ritualized. We bought our Levis just a little bit long, and turned up only the bottom seam.” – Jim Moore

Trends in Fifties fashion also paralleled trends in aviation and automobile design, and scientific developments in atomic and space research.

Trends in Fifties fashion also paralleled trends in aviation and automobile design, and scientific developments in atomic and space research.

From the late 1940s to the late 1950s, GM designer Harley Earl looked to the aerodynamic qualities of military aircraft as inspiration for his automotive designs. The military’s Douglas F4-D Skyray, with its angled delta wing shape and aerodynamic styling, was a direct influence on his design of the popular 1955 Chevy.

Most automobiles from the mid-to-late 1950s sported variations on the bomber theme. They ranged from bomb-shaped “dagmars,” named after a busty blonde late-night television bombshell, to rocket-shaped taillights and fins on the rear fender. Automotive company logos, hood ornaments and even household appliances reinforced these themes, using wings and boomerang shapes as design elements.

Fashions were also designed to emphasize motion and speed. Angular peplums and sashes flew dramatically alongside the wearer, and echoes of the angled boomerang shape were present in sheath-shaped dresses and angular, wide-cut necklines. Even women’s shoes presented the foot as a missile-like shape, with impossibly slender, spiked heels providing the liftoff for a speedy ascent.

Atomic Albuquerque

While research and testing in New Mexico brought us into the Atomic Age, advancements in rocketry, satellite and computer technology inaugurated the Space Age. By the end of the 1950s, Albuquerque claimed more Ph.Ds per capita than any other city in the nation. Many were engineers who contributed their knowledge during what is considered by many to be the greatest period of scientific advancement in our history.

From their research, light weight, water-resistant, and durable synthetic materials entered the commercial market in the form of household goods and clothing. Synthetic fabrics, metallic threads, and durable plastics were all the rage for clothing and accessories. Caught up in the excitement of progress, companies borrowed atomic models for product designs and logos; space ships and planetary orbits for neon signage. These space-age motifs even burst their way onto fabric patterns.

From their research, light weight, water-resistant, and durable synthetic materials entered the commercial market in the form of household goods and clothing. Synthetic fabrics, metallic threads, and durable plastics were all the rage for clothing and accessories. Caught up in the excitement of progress, companies borrowed atomic models for product designs and logos; space ships and planetary orbits for neon signage. These space-age motifs even burst their way onto fabric patterns.

The Consumer Explosion

“In '56 or '57 I bought what I thought were beautiful and stylish “cat-eye” glasses. They were black with diamonds encrusted all around them. I thought that I was pretty glamorous when I had them on. When my husband saw them he made fun of me and thought I looked a little too ‘Hollywood.’” – Olga Sandoval

By the 1950s, factories and designers were in full swing. Television and magazine advertisements blasted household products into the consciousness of the American consumer. There was a seemingly never-ending variety of products available in Albuquerque – all promising to simplify our lives, provide more family time, make us more beautiful or handsome, or reinforce the image of being forward-thinking and progressive.

Penney’s, Sears and Montgomery Wards were all located downtown, and carried huge inventories of products and clothing that could also be ordered through catalogues. Hardware and appliance stores, wedding boutiques, jewelry stores, and specialty shops such as Mrs. Bartley’s and Bertha’s Hat Shop, also thrived along Central Avenue’s business district.

Korber’s Hardware was stocked with every time saving kitchen gadget in existence. Pots and pans, utensils, coffeepots, and the very latest appliances could be purchased there. Korber’s also carried California Modern dinnerware and the popular Heywood-Wakefield furniture line.

Korber’s Hardware was stocked with every time saving kitchen gadget in existence. Pots and pans, utensils, coffeepots, and the very latest appliances could be purchased there. Korber’s also carried California Modern dinnerware and the popular Heywood-Wakefield furniture line.

Albuquerque had its own furniture businesses, too, including American Furniture, Galbreth’s and the Franciscan Furniture Company. Their products were marketed to the Albuquerque consumer, but also to the hotels and restaurants that dotted Route 66.

Top Drawer: Where to Shop!

“When my husband needed a new suit I would go to Kistler’s and…pick out two or three suits. Then Kistler’s would let me take them home on approval. No money passed hands. My husband would pick out the suit he liked. Then he would return the suits, and have them hem the one he was going to buy.” – Peggy Poulsen

“I’d go to New York and then back to Albuquerque, and would always end up buying my shoes at Paris Shoes.” – Shirley Morrison

Kistler-Collister opened as J.H. Collister in 1909, at the corner of Central Avenue and Second Street. By the 1950s they carried fabric, linens, bridal wear, and clothing for children and adults. Later they specialized in daytime and formal fashions, lingerie, and hats. The company began saving examples from the sales floor, preserving them in the store’s fur vault. They were often used for anniversary displays and special store functions, and even family proms and weddings. In 1995, the year Kistler-Collister closed its doors, owner Ken O’Dell donated the collection to the Museum.

Kistler-Collister opened as J.H. Collister in 1909, at the corner of Central Avenue and Second Street. By the 1950s they carried fabric, linens, bridal wear, and clothing for children and adults. Later they specialized in daytime and formal fashions, lingerie, and hats. The company began saving examples from the sales floor, preserving them in the store’s fur vault. They were often used for anniversary displays and special store functions, and even family proms and weddings. In 1995, the year Kistler-Collister closed its doors, owner Ken O’Dell donated the collection to the Museum.

Car-Lin Casuals, located at 205 West Central Avenue, was another local favorite. Owner Jack Lebby named the shop after his daughters, Carol and Linda. Clients had their favorite sales staff, who would bring water and soda to their dressing rooms as they tried on their favorite clothes. Carol Lebby was said to have a photographic mind; she memorized what clients had in their closets and created outfits to fill their individual needs.

Stromberg’s was a high end men’s shop featuring suits, tuxedos, and accessories. The popular store opened in 1934 at 224 West Central Avenue, then opened a second location at the Nob Hill Business Center in 1947. Additional locations were added as Albuquerque’s Northeast Heights increased in population. Their final location in Park Square Plaza, near Coronado Mall, closed in 2002.

Stromberg’s was a high end men’s shop featuring suits, tuxedos, and accessories. The popular store opened in 1934 at 224 West Central Avenue, then opened a second location at the Nob Hill Business Center in 1947. Additional locations were added as Albuquerque’s Northeast Heights increased in population. Their final location in Park Square Plaza, near Coronado Mall, closed in 2002.

Paris Shoes, founded in 1904 by Italian immigrant Pompilio Matteucci, opened first as a shoe repair shop. By the 1950s the store carried shoes, handbags and other accessories and moved to Third and Central, with a second location in Nob Hill. Paris Shoes was a nationally known and respected company, and was highly regarded by shoppers for their extra-special customer service. Employees from Kistler-Collister and Car-Lin would personally bring their clients’ choices over to Paris, in order to create the perfect accessory match for them. Eventually Paris Shoes had five locations; the Central Avenue shop closed in 1990.

Albuquerque Chic

“That was the wonderful thing about Albuquerque…all the newcomers were welcome. When you came to New Mexico, you had to have a fiesta dress.” – Shirley Morrison

“Emily Ann had a dress shop in Old Town, and her specialty was fiesta dresses. You could get a fiesta dress made in your choice of colors and sizes.” –Jim Clements

“Native women also made their own clothes. The Diné women would come in and sell clothes, cloth and woven goods, jackets, velvets, broomstick skirts, and concha belts at the corner of Rio Grande and the Plaza.” – Emma Moya

“The Western look was more of a Texas than New Mexico thing. If you were dressing up for a Western party, you would wear a fiesta dress or a western shirt and jeans, but not a cowgirl outfit.” – Shirley Morrison and Terry Salazar, 2003

Many Albuquerque citizens could not afford The New Look; instead, they bartered for necessary items, wore hand-me-downs, or re-fashioned new clothing from older styles. Downtown shops carried patterns, fabrics and sewing notions that allowed the resourceful to create their own clothing according to the new designs marketed by Vogue, McCall’s, Simplicity and others.

One of the most enduring elements of local Albuquerque fashion is the “fiesta dress.” Worn to the annual San Felipe de Neri Fiesta in Old Town, as well as other celebrations, fiesta dresses were specialty items available in shops right off Old Town Plaza and on Central Avenue. They were designed and sewn by hand from colorful cotton fabrics, adorned with bright “rick-rack” trim, and usually worn with high heels.

One of the most enduring elements of local Albuquerque fashion is the “fiesta dress.” Worn to the annual San Felipe de Neri Fiesta in Old Town, as well as other celebrations, fiesta dresses were specialty items available in shops right off Old Town Plaza and on Central Avenue. They were designed and sewn by hand from colorful cotton fabrics, adorned with bright “rick-rack” trim, and usually worn with high heels.

The traditional Diné (Navajo) velvet outfits and jewelry worn as uniforms by the Fred Harvey Company’s Indian Detours couriers also became increasingly popular with local designers. As in earlier decades, Native American women sold traditional hand made clothing and silver jewelry at the Plaza and at the Santa Fe Railway depot. Native clothing and jewelry could also be found in shops like the Covered Wagon, Wright’s Indian Art, Maisel’s, and the curio shop at C.G. Wallace’s De Anza Motor Lodge.

Inspired by the blending of traditional Native American and Hispanic dress with a romanticized and somewhat mythical “Western Style,” New Mexico invented its own “new look,” which fit perfectly with the primary components – the long, full skirt and nipped-in waist – of the New Look. Its key elements included “broomstick” (twisted), pleated and tiered skirts, fitted blouses, plenty of Native American jewelry, fringed or woven jackets, cowboy boots and hats, bola ties, and blue jeans. Today the look is described as “Southwest Style,” “New Mexico Style,” “Santa Fe Style,” or “Albuquerque Chic.”

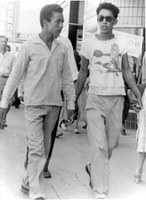

Many teens and college students went for a more rebellious appearance, wearing flouncy “poodle” or “circle” skirts, bobby socks, saddle oxfords, denim jeans, pullover shirts, ponytails, and “pompadour” or “crew” cuts. It was not uncommon to see a mixing of all of these styles on the streets of downtown Albuquerque.

Many teens and college students went for a more rebellious appearance, wearing flouncy “poodle” or “circle” skirts, bobby socks, saddle oxfords, denim jeans, pullover shirts, ponytails, and “pompadour” or “crew” cuts. It was not uncommon to see a mixing of all of these styles on the streets of downtown Albuquerque.

Good Times

“The Kistler-Collister fashion show featured local Albuquerque models who were coached on how to wear the fashions. A lot of them didn’t have the spike shoes that were needed, so Paris pitched in and helped by lending them the shoes. Kistler’s had an invitation list a mile long, developed from the list of clients who had accounts there.” –Henrietta Loy

“We didn’t live far from the Old Town Society Hall, which was located near where Central and Rio Grande are today. Everybody used to go dancing. Tommy Dorsey played there once. There was a mirror ball, and stars on the ceiling.” – Roy Dominguez

“Elvis Presley would come in from California through Gallup in his pink Cadillac and watch the lights of Albuquerque from the top of Nine Mile Hill. Everybody knew when he was coming, and we would watch him at the filling station.” – Emma Moya

The Fifties brought numerous opportunities for fun. Favorite destinations included the Albuquerque Civic Center, Alvarado Hotel, Old Town with its Society Hall and numerous restaurants, Tingley Field, the Armory, and Hilton’s fabulous La Posada Hotel. In 1955 Kistler-Collister held a fashion show at La Posada; it was a grand opportunity to witness the very latest fashions in motion.

In 1956, the City of Albuquerque celebrated the 250th anniversary of its founding. Honored guests included the 18th Duke and Duchess of Alburquerque, Spain, who presented the city with a 17th century repostero (wall hanging with coat of arms) belonging to the 8th Duke of Alburquerque. Festivities lasted for weeks, bringing opportunities to promote the city and its business community.

In 1956, the City of Albuquerque celebrated the 250th anniversary of its founding. Honored guests included the 18th Duke and Duchess of Alburquerque, Spain, who presented the city with a 17th century repostero (wall hanging with coat of arms) belonging to the 8th Duke of Alburquerque. Festivities lasted for weeks, bringing opportunities to promote the city and its business community.

Family occasions brought additional opportunities to dress up. Weddings and funerals sent folks to Central Avenue for appropriate attire. One always dressed for religious services, airline and train travel, jaunts to the theatre or movie shows, and even shopping trips downtown.

Family occasions brought additional opportunities to dress up. Weddings and funerals sent folks to Central Avenue for appropriate attire. One always dressed for religious services, airline and train travel, jaunts to the theatre or movie shows, and even shopping trips downtown.

Concerts and performances were always enjoyable. Among the numerous performers who played Albuquerque during the Fifties were Tommy Dorsey (Old Town Society Hall and La Loma Dance Hall), Les Brown (UNM Stadium), and Patsy Cline (The Armory). The 1956 Elvis Presley concert was a particularly controversial event, prompting animated family discussions over whether the “kids” would be allowed to attend.

From the New Look to the Wet Look

“All the shops had very similar expansion plans. We all had downtown locations, and then expanded in the Sixties and Seventies to either Winrock Mall or Coronado Mall.” – Bob Matteucci, Sr.

“The Sixties was a big era for style changes, especially the late Sixties. At Paris Shoes, we carried go-go boots and sandals. The dressier styles declined, and people began to dress more relaxed and casual.” – Bob Matteucci, Sr.

“Suburban residential growth created business opportunities far from downtown. Both local and national companies responded, building suburban stores, offices, and recreational venues such as bowling lanes near the new neighborhoods. This development of new commercial districts began to limit the goods and services available downtown, further influencing shoppers to buy in the ‘burbs.’” – Ed Boles

By 1960, the New Look had reached the end of its era. A more socially conscious Albuquerque, fueled in part by an exploding UNM student population, looked to fashion as a way to express a desire for change. For many, concerns about discrimination and equal rights, care for the sick and poor, and the politics of Vietnam held greater importance than “keeping up with the Joneses” through mass consumerism. With all eyes on the Kennedy family as models for social change, First Lady Jackie Kennedy emerged as a trend-setter for the shorter hemlines and sleeveless dresses inspired by designer Oleg Cassini. In men’s fashion, the Beatle Look caught on like wildfire, inspiring many to grow their hair and sport colorful bell-bottomed jeans.

By 1960, the New Look had reached the end of its era. A more socially conscious Albuquerque, fueled in part by an exploding UNM student population, looked to fashion as a way to express a desire for change. For many, concerns about discrimination and equal rights, care for the sick and poor, and the politics of Vietnam held greater importance than “keeping up with the Joneses” through mass consumerism. With all eyes on the Kennedy family as models for social change, First Lady Jackie Kennedy emerged as a trend-setter for the shorter hemlines and sleeveless dresses inspired by designer Oleg Cassini. In men’s fashion, the Beatle Look caught on like wildfire, inspiring many to grow their hair and sport colorful bell-bottomed jeans.

With hemlines up and heel heights down, designers once again played with shape and pattern inspired by artists such as Peter Max and Andy Warhol. Wild colors and flowers were hip. Shoe styles changed drastically, as designers experimented with ideas for sandals and “go go” boots made from “wet look” vinyl and plastics. Jewelry, formerly used primarily as a means to enhance beauty, became a way to convey social and political messages. Hats, gloves, and hankies all but disappeared.

With hemlines up and heel heights down, designers once again played with shape and pattern inspired by artists such as Peter Max and Andy Warhol. Wild colors and flowers were hip. Shoe styles changed drastically, as designers experimented with ideas for sandals and “go go” boots made from “wet look” vinyl and plastics. Jewelry, formerly used primarily as a means to enhance beauty, became a way to convey social and political messages. Hats, gloves, and hankies all but disappeared.

By the mid-1960s, many of Albuquerque’s downtown shopping establishments established second locations nearer to the suburbs, or closed altogether. With the opening of Winrock and Coronado Malls and the completion of the “Big I” highway interchange, shoppers shifted their attention – and their wallets – away from Central Avenue. Car-Lin Casuals, Jeanette’s, Kistler-Collister, Korber’s, the Old Town Dress Shop, Paris Shoes, Stromberg’s and others are no more, but they live on in our memories – and often, in our closets.