Route 66: Radiance, Rust & Revival on the Mother Road

Conceived in honor of the 90th anniversary of Route 66, this exhibition celebrates the art, history and popular culture of the iconic Mother Road.

'Route 66: Radiance, Rust, and Revival on the Mother Road'

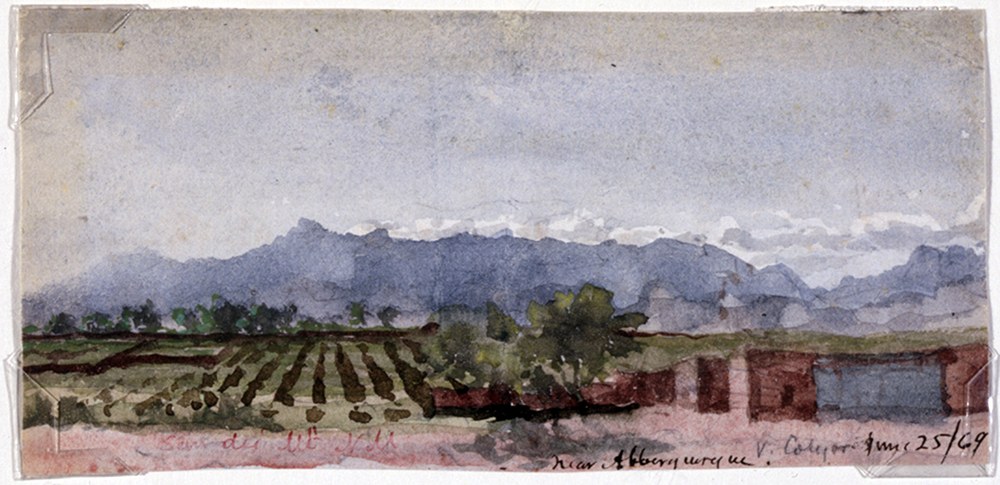

Albuquerque Progress Collection

Gift of Albuquerque National Bank

PA1980.187.338

From her hotly debated beginnings to her decades-long role as a pathway for adventurers, migrant workers, post-war veterans, tourists, hippies and sentimental souls, Route 66 has fascinated and engaged us, and compelled us to follow her beaten, crumbling path. Her very existence today demonstrates that her legacy is not just in the past, but that she is part of our present reality. Conceived in honor of the 90th anniversary of Route 66, this exhibition celebrates the art, history and popular culture of the iconic Mother Road.

Too often the history of Route 66 in Albuquerque has been overlooked, even though our city boasts, at 16 miles, the longest single-city urban stretch of the highway in the nation. We are also the only place on the Mother Road where the highway crosses herself; where travelers can trace her winding routes in four different directions!

This exhibition explores the story of Route 66 in New Mexico and the Albuquerque area, set in the context of significant national events and enhanced by the stories of Albuquerque residents and visitors.

Jar, Agua Fria Glaze-on-red, 1350-1450

Ward Alan and Shirley Jolly Minge Collection

PC1998.22.17

Beginnings

From time immemorial, the geography of our continent has influenced how we move across it. From the Bering Land Bridge to La Bajada Hill, from the Mighty Mississippi to the Rio Grande and Colorado Rivers, land forms and river systems have created natural conduits allowing for migration, trade, and the spread of ideas between cultures.

European countries sought to explore North America and find a route to the Indies for hundreds of years before Spanish, British, and French explorers began documenting our continent. The earliest 16th-18th century European explorers took routes into the interior from North America's southwestern, southern, southeastern, and northeastern borders. But the Great Southwest did not exist as we know it; by the 18th century, settlers understood that La Villa de Alburquerque sat squarely in New Spain's "Far Northeast."

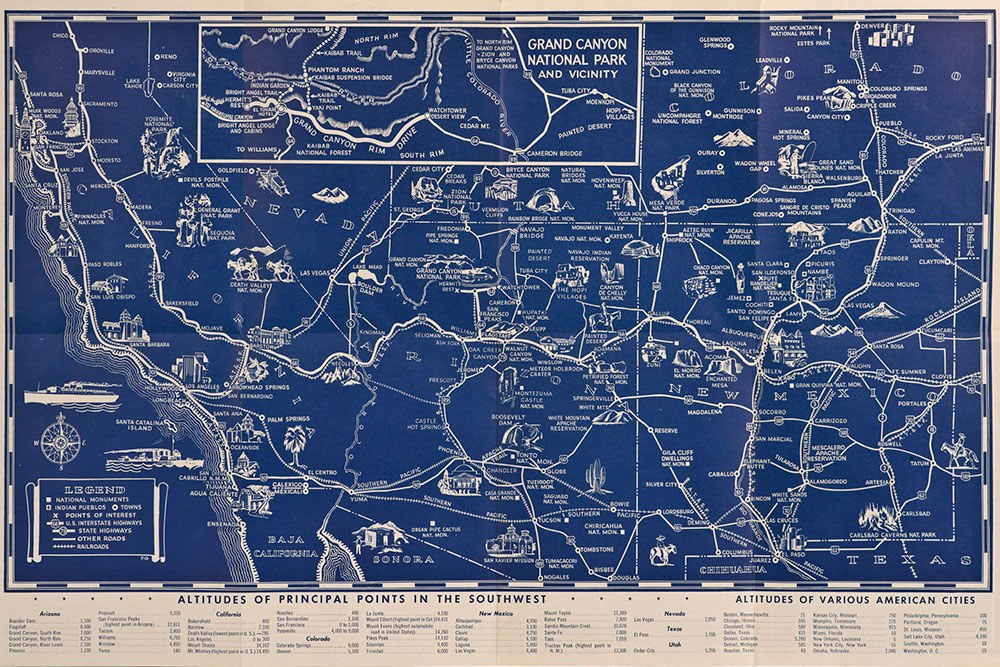

"San Dei Mountains near Alberquerque", 1869

Watercolor painting on paper

2 1/2 x 5 in.

Museum Purchase, 1983 General Obligation Bonds

1985.30.12

Crossroads

"The road we travelled passes down through the settlements of New Mexico for the first hundred and thirty miles, on the east side of the Rio del Norte. Nevertheless, as there was not an inn of any kind to be found upon the whole route, we were constrained to put up with very primitive accommodations." –Santa Fe Trail merchant Josiah Gregg, 1844

The arrival of Lt. Zebulon Pike's exploration party in 1807 signaled the launch of numerous American initiatives to explore, document, hunt and trap, and acquire lands in our region. In 1841, members of the Texas-Santa Fe Expedition journeyed here, ostensibly to trade, but instead endured a savage repetition of Pike's march south to México and caused a land dispute resolved only by the Compromise of 1850. But in 1846, Colonel Stephen Kearny marched right into Santa Fé and Albuquerque, claiming New Mexico for the United States with nary a shot.

Some explorers, such as Lorenzo Sitgreaves and Vincent Colyer, sought to document Native American villages, plants and animals, and the visual beauty of the southwestern landscape. Others, such as Lt. Edward Fitzgerald Beale, ferreted out stories of the California gold fields, conducted military campaigns or blazed new military roads and railroad lines.

Their newly blazed roads included the east-west route of the Santa Fe and Old Spanish Trails, and the north-south route of the Camino Real. Later called the Chihuahua Trail, this route overlaid the ancestral trails and eventually became the National Old Trails Road and Highway 66. Their efforts resulted in improved stream crossings and bridges between Fort Smith and Albuquerque, and road construction west of Albuquerque. Beale's men called the sandhills west of town "the worst part of the road to California."

Alfred S. Waugh (c. 1810-1856)

Portrait of Manuel Armijo, 1846

Dr. Ward Alan and Shirley Jolly Minge Collection

Museum purchase, 1995 Government Obligation Bonds

1998.22.51

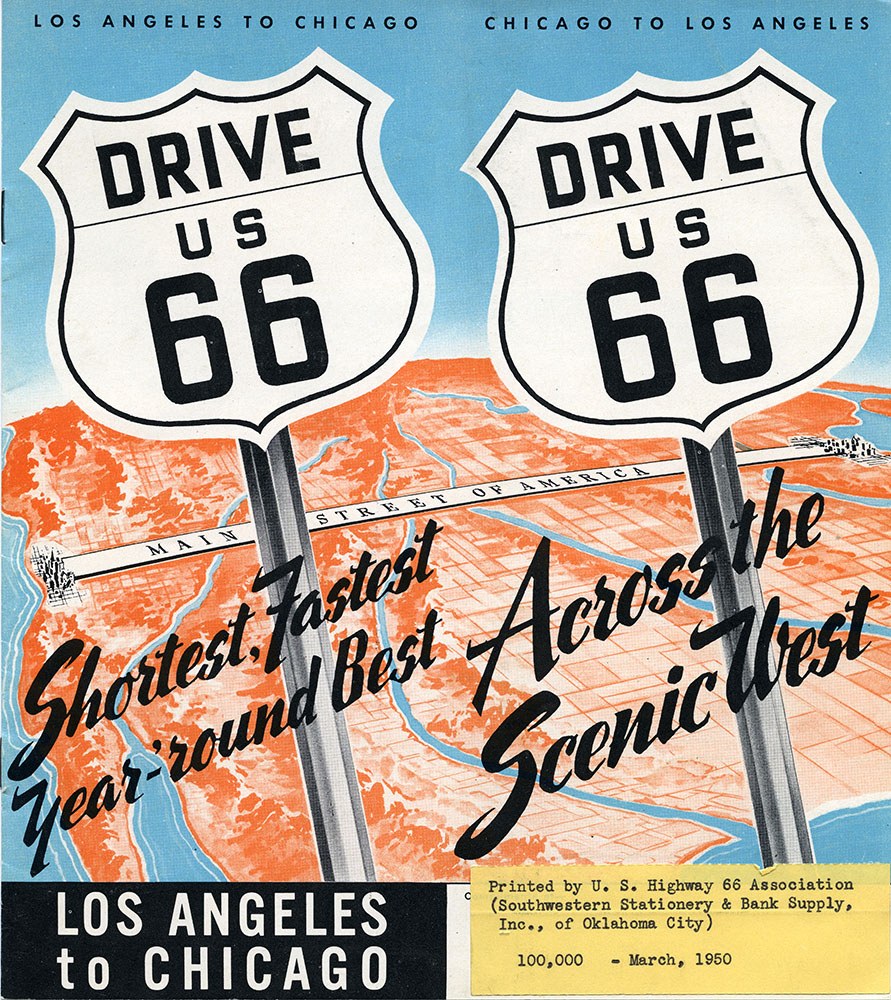

Illustrated Map of the Great Southwest, 1946

Fred Harvey

Paper, ink

PA2008.7.1

Industrial Invasion

"... Today people traveling by auto ... find U.S. 66 is the most direct road to the Pacific coast and likewise to all points in the great Southwest. I challenge anyone to show a road of equal length that traverses more scenery, more agricultural wealth, and more mineral wealth than does U.S. 66." — Cyrus Avery, Father of Route 66

The arrival of the railroad changed everything, giving America an inexpensive and relatively quick way to find new jobs and start new lives. No longer dependent on freighting via stage coach, entrepreneurs shipped the tools and equipment needed to feed the massive appetites of industries made possible by railroad transportation. Locally, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway and its subsidiaries provided New Mexico with direct connections to the East and stimulated economic growth. Easterners and immigrants seeking work poured into town by the thousands every week.

In Albuquerque, the largest employers were the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, American Lumber Company, Albuquerque Foundry, and Southwest Brewery and Ice. From the mid- to late 19th century, American Lumber harvested wood from the Sandia Mountains and the forests around Pecos. Changing its name to McKinley Land and Lumber in 1905, the company operated the Zuni Mountain Railroad near Thoreau and began logging the forests around Zuni Mountain and Mount Taylor.

By the mid-20th century, workers were moving to New Mexico from all over the world, including Canada and France, to work in the mines. Workers took trains to Albuquerque, then rode by horse, stage coach, or buckboard to the territory's various mines including the Señorita copper mine near Gallina, the Santa Rita copper mine near Hurley, and coal mines in Gallup.

In 1950, Navajo sheep herder Paddy Martinez found uranium-bearing rock near Grants. Miners such as Jack Farley, Dana Gebel, and Leroy Hessler worked 16 hours a day, seven days per week, in hot and hazardous conditions until the mines closed.

Leon Trousset's depiction of New Albuquerque, built just east of the railroad line, emphasizes the north-south orientation of the central Rio Grande Valley. The railroad laid its track on relatively high ground near Front (First) Street, avoiding the periodic flooding of Old Town.

Leon Trousset (1838-1917)

"New Town", 1885

Oil on canvas

Gift of Jim McCanna

1994.26.1

Gift of Ray and Daniel Bandel

PA1977.131.98

Paving the Nation

"Although my father's parents were from California, he moved to Albuquerque where he was raised in Martineztown. My father [Richard Gutierrez] in his early years worked on the route with Skousen Construction Company ... . and when the construction wound up its stint in Santa Rosa, my father opted to stay and raise his family." — Richard Gutierrez, 2000

By the early 1900s, the West was becoming a civilization on wheels. Southern California most reflected this lifestyle, but other areas began to follow suit. Over the next half century, automobiles would dictate how western cities were configured, where residences and businesses would be built, and how families would move. The majority of western settlers hailed from the rural Midwest and the South. They wanted a rural world within a city, but without the isolation, and the automobile could help them achieve that goal. America began an affair with the automobile that thrives to this day.

Route 66 had its beginnings in the Good Roads Movement, a country-wide effort to improve roads for bicyclists and, later, automobile enthusiasts. The movement gained national prominence when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. Efforts to unify state highways resulted in the National Old Trails Highway, created to provide a unified, if mostly unpaved, 2989-mile long road from Baltimore to Los Angeles.

Central Avenue underpass under construction, 1937

Museum purchase

PA2014.1.25

Avery, Hannett & Tingley

In Albuquerque, much of the National Old Trails Highway was unpaved. It ran along U.S. 85 and 4th Street north of town, and Isleta Boulevard south of town, avoiding the basalt escarpment west of the Rio Grande and the lava fields of the "malpais" (badlands). But by 1926, significant portions of the old highway remained dangerous and difficult, and only 800 miles were paved.

Oklahoman Cyrus Avery was instrumental in the creation of a new national highway system out of the country's cobbled-together auto trails; the highway was commissioned in 1926. The Joint Board of Interstate Highways' decision to assign the number 66 to the national highway, after 60 was unobtainable, gave way to a certain fondness for double digits. The route ran through eight states including New Mexico.

Controversy persisted, however. By the 1930s, many — including New Mexico Maintenance Superintendent Clyde Tingley — believed that the route could be shortened and realigned east-west. Governor Arthur Hannett, furious for having lost his 1925 bid for re-election, ordered construction of a new highway between Santa Rosa and Moriarty to be completed by the end of his term.

Irate citizens tried to delay the project by "sugaring" the construction equipment gas tanks and "sanding" the engines, and the crews had to cut through 27 miles of piñon forest near Moriarty, but "Hannett's Joke" (east of Albuquerque) and the "Laguna Cutoff" (west of Albuquerque) became part of the new Route 66 by 1937. The shortcuts reduced road-weary drivers' highway travel by more than 100 miles, and diverted tourist dollars straight into our city.

In his memoirs, Governor Arthur Hannett recalled that he conceived of the shorter, east-west alignment by placing a ruler on the map between Santa Rosa and Gallup. However, Highway Maintenance Supervisor Clyde Tingley may have first proposed the idea in a letter to Hannett dated June 9, 1925. He provided a hand drawn map and suggested that the route would eliminate 30 miles, five railroad crossings, and two bridges.

Route 66 sign, 1940s

Steel, paint

Museum purchase

2013.8.1

Motoring through the Land of Sunshine

"Wheel of Fortune came about as the result of a game that my sister and I used to play in the car ... My parents would take us all the way to Carlsbad Caverns to see the bats fly out or something equally exciting." — Merv Griffin, "Making the Good Life Last", 2003

By the 20th century, town founders and the Commercial Club were marketing Albuquerque as a destination. Tuberculosis patients flocked here from large cities for our sunshine and clear air, with many staying to found businesses, get into politics, and form arts organizations. Meanwhile, Fred Harvey and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway invited newcomers to experience the "exotic Southwest" and become acquainted with Native people through their artisanship and social/ceremonial events.

Route 66 wound its way through eight states: Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California, for 2,448 miles. There was (and is) plenty of scenery to experience along the way: the stunning urban architecture of Chicago, flat grasslands of the Midwest, rugged mountains and color-drenched sunsets of the Southwest, and sparkling, sandy beaches of the California coast.

Artists getting their first taste of the West traveled by train and automobile to capture America's beautiful scenery, while tourists learned about our country's heritage through aggressive marketing by the National Park Service. By World War II, tourism had become a major industry in the West.

Advertisement, "Drive US 66", 1950

US Highway 66 Association

E488a

Charles Craig, 1846-1931

"Isleta, 1907

"Oil on canvas

Museum purchase, 1985 General Obligation Bonds

1986.21.1

Eudora Montoya, Santa Ana, 1905-1996

Canteen from Sewell's Indian Arts, Old Town, 1940s-1950s

Clay, natural pigments

Gift of Rita Anderson and David Starr, daughter and son of Eleanor B. Sewell

2006.26.60

New Mexico dust cloud, 1935

Walter Collection

Museum purchase, Government Obligation Bonds

PA1999.61.14

Twin Disasters

"The woman was hugging a dead chicken under a ragged coat. When I asked her where she had procured the fowl, first she told me she had found it dead in the road, and then added in grim humor, "They promised me a chicken in the pot, and now I got mine." " — Oscar Ameringer, 1931"

"Shortly after Route 66 opened, two major catastrophes decimated our country. The Great Crash of 1929 radically changed the destinies of countless Americans, lingering for over a decade. The Depression's impact was severe in industrialized and agricultural areas, but the effects were most acutely felt in the West, and the westward population flow abruptly stopped. In New Mexico, desperate workers moved from rural communities to larger urban centers, like Albuquerque, to find employment."

"Added to the complexity of the Depression years was the Dust Bowl migration of the mid-late 1930s. Millions of Midwestern refugees attempted to escape the technological changes in agriculture that eliminated jobs and turned irresponsibly farmed fields into barren wastelands, as drought, dust, and insect swarms annihilated the region."

New Mexico, especially the northeastern quadrant, was just as hard hit by the Dust Bowl. Farmers and their families — handkerchiefs over their noses and mouths — began evacuating to other states looking for clear skies and clean crops. Migrant travelers perceived the end of the rainbow to be California's central valley, where oranges fell like rain from the trees, and a poor man could achieve the American dream.

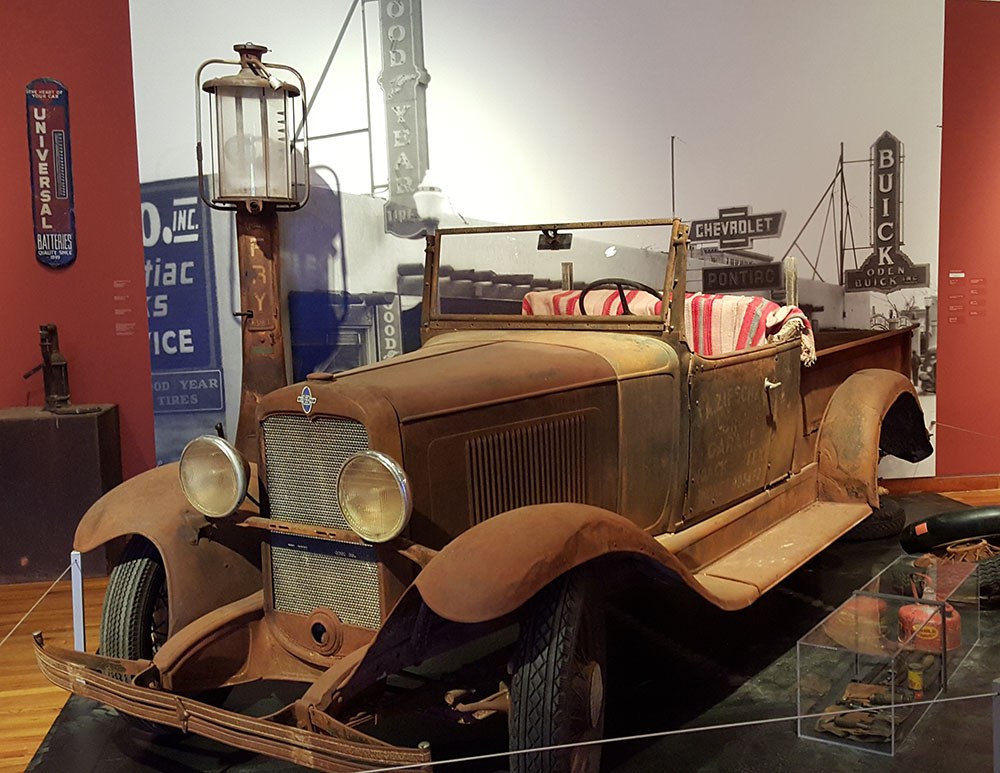

Migrant worker breakdown scene

Courtesy Jay Hertz

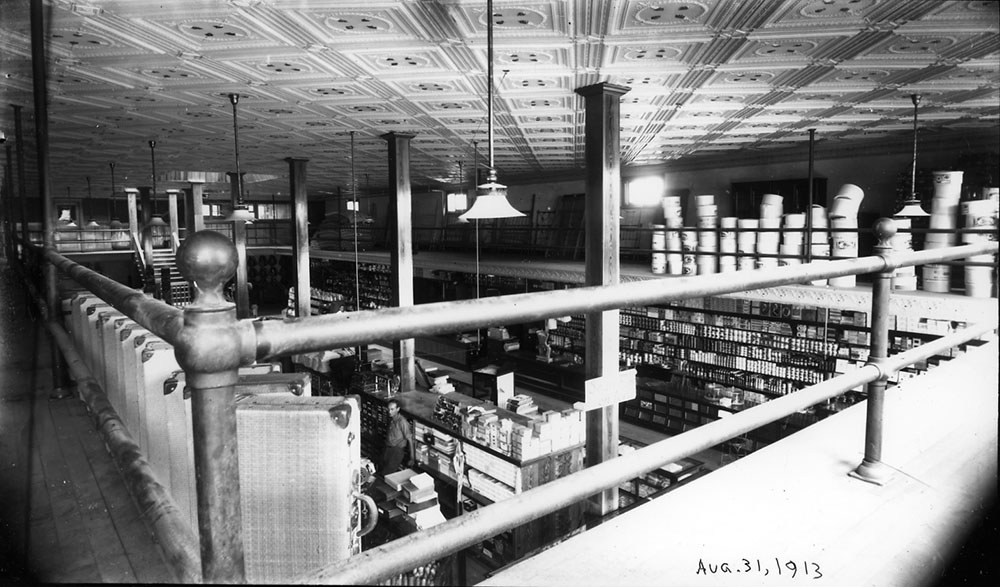

Interior of Bernalillo Mercantile Co., 1913

Charles Lummis

PA1985.4.1

Tin Can Tourists

"... We had a lot of the people from Texas and Oklahoma and back east, Kansas, that were headed west to California ... they'd stop here, and some would be completely out of food and money ... so what local people would do, they would give 'em enough money to get from here to Grants." — Lee Marmon, Laguna, "Route 66 and Native Americans", 2009

By 1935, many families were forced to abandon their dust-destroyed farms and seek work elsewhere. Commonly referred to as "tin can tourists," these migrant families arrived in California from the Great Plains in rusted hulks on tires, packed with their personal belongings and supplies for camping en route.

The Dust Bowl migration was the largest in American history within a short period of time; between 1930 and 1940, approximately 3.5 million people moved out of the Plains states. Arriving in California exhausted, many migrants were shocked to discover the actual working conditions. About 90% left California after a few months. Many, finding New Mexico to their liking, remained in the Land of Enchantment.

Novelist John Steinbeck captured the plight of the Dust Bowl migrants in his book, "The Grapes of Wrath" (1939). The book was an instant hit as was the 1940 film adaptation directed by John Ford, the music of singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie, and the works of Farm Service Administration photographers Dorothea Lange and Russell Lee. These works focused international attention on Route 66.

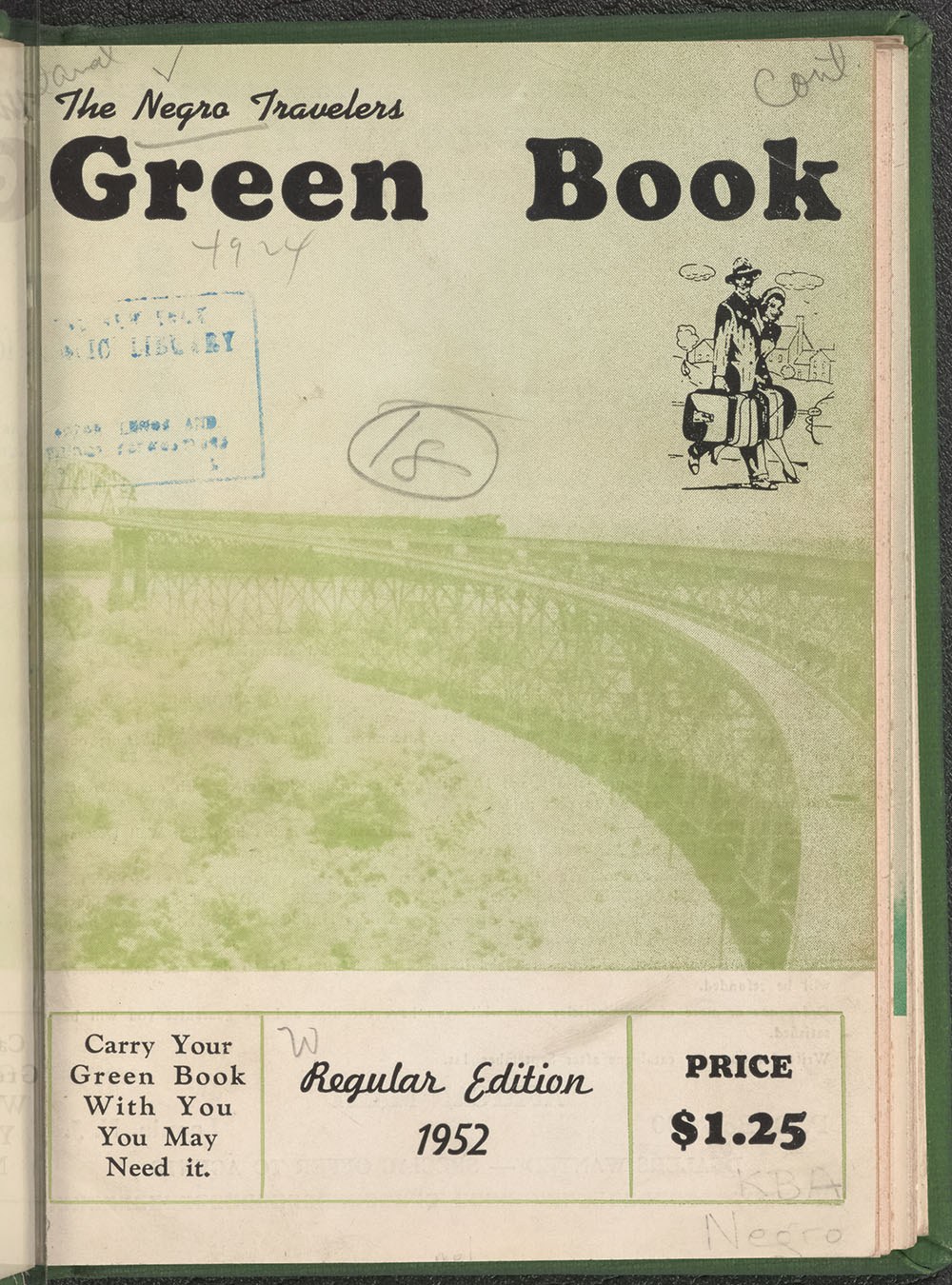

Victor H. Green

"The Negro Travelers' Green Book", 1952

Courtesy New York Public Library Digital Collections

Travel is Fatal to Prejudice

"There would be no restaurant for us to stop at until we were well out of the South, so we took our restaurant right in the car with us... Stopping for gas and to use the bathroom took careful planning. Uncle Otis had made this trip before, and he knew which places along the way offered 'colored' bathrooms and which were better just to pass on by." — social commentator John Lewis, 1951"

"The Negro Travelers' Green Book," published 1936-1964 by Victor H. Green, provided African American tourists with the information they needed to travel comfortably. In Albuquerque, safe havens included the Alvarado Hotel, Aunt Brenda's Restaurant, Bob's Apartment Motel, Bon Ton Restaurant, Cactus Motel, Dutch Motel, Greyhound Inter-State Restaurant, Fred Harvey Airport Restaurant, Ideal Hotel, Kate Duncan Tourist Home, South Side Barber Shop and Rooms, and the Mrs. W. Bailey Tourist Home.

Black travelers often had to carry buckets or portable toilets in the trunks of their cars because they were usually barred from bathrooms and rest areas. Gasoline was difficult to purchase because of discrimination at gas stations. To avoid such problems, African American families often packed meals and carried containers of gasoline in their cars.

In California, migrant workers from Oklahoma, Arkansas, and other states also found themselves discriminated against. Californians resented the massive influx of rusted jalopies and the destitute families, whose very presence drove down the meager migrants' wages and living conditions.

"Woody Guthrie, Half-length Portrait, Facing Slightly Left, Holding Guitar," 1943

World Telegram photo by Al Aumuller

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, #95503348

Steinbeck & Guthrie

"I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world and that if it has hit you pretty hard and knocked you for a dozen loops, no matter what color, what size you are, how you are built, I am out to sing the songs that make you take pride in yourself..." — Woody Guthrie

John Steinbeck gave himself ninety days to write "The Grapes of Wrath" as his wife typed the manuscript. The novel won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and was also cited when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962. In the novel the Joad family migrates to California, realizing that nothing is left for them in Oklahoma, only to find the state oversupplied with labor.

John Ford's 1940 adaptation of John Steinbeck's "The Grapes of Wrath" starred Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, and John Carradine. Many scenes were shot in New Mexico including various locations in Gallup, and a bridge over the Pecos near Santa Rosa where Tom Joad watches a train rumble into the sunset.

Singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie composed thousands of songs during his lifetime. Some of these lyrics are in the form of notebooks, journals, or loose sheets collected by Guthrie which he bound himself. He is most well-known for his Dust Bowl songs including "The Great Dust Storm", and especially for "This Land is Your Land" which still inspires patriotism today.

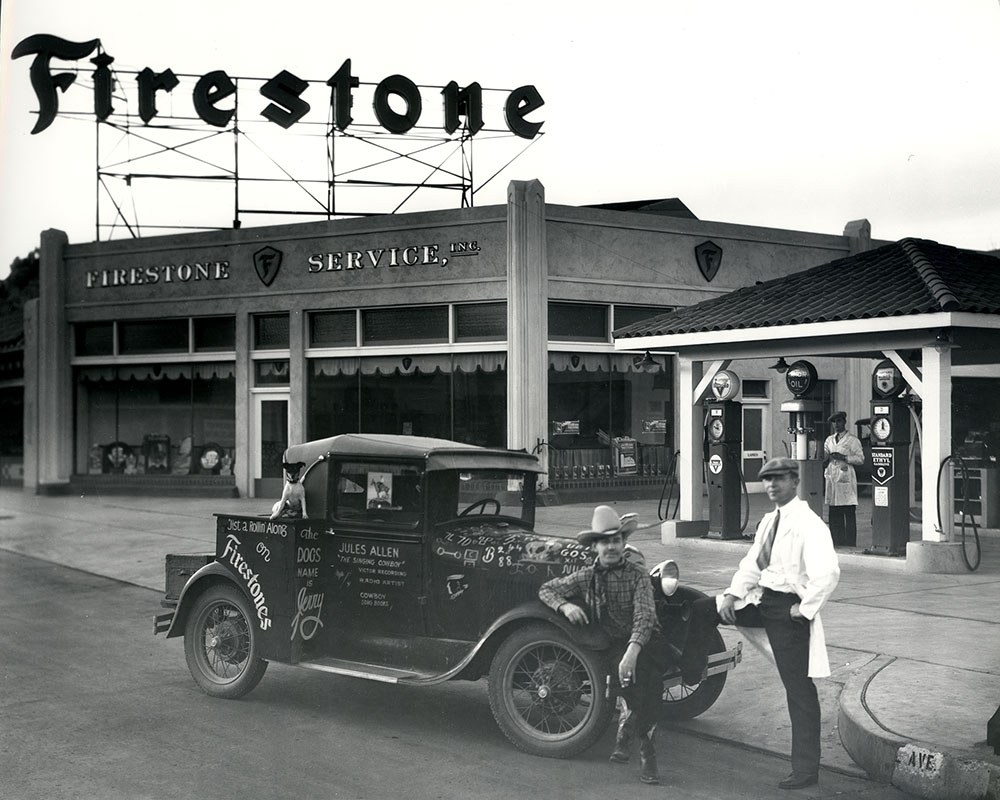

Jules Allen in front of the Firestone service building with his dog Jerry, 701 W. Central Avenue, c. 1931

The Brooks Collection. A Gift of Channell Graham.

PA1978.151.327

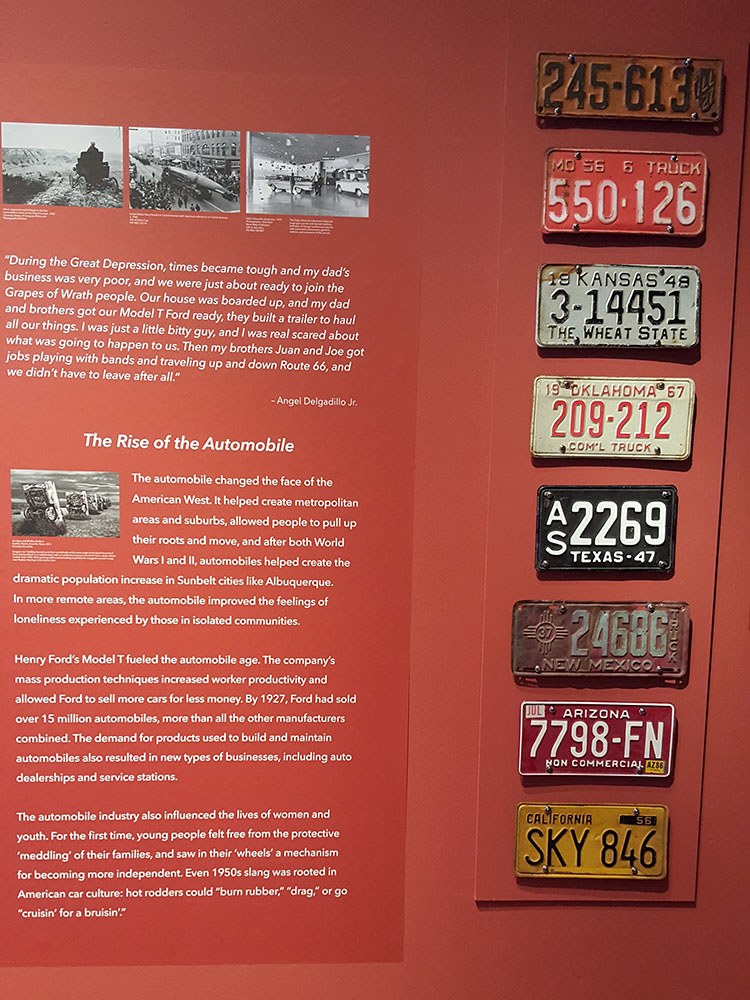

The Rise of the Automobile

"During the Great Depression, times became tough and my dad's business was very poor, and we were just about ready to join the Grapes of Wrath people. Our house was boarded up, and my dad and brothers got our Model T Ford ready, they built a trailer to haul all our things. I was just a little bitty guy, and I was real scared about what was going to happen to us. Then my brothers Juan and Joe got jobs playing with bands and traveling up and down Route 66, and we didn't have to leave after all." — Angel Delgadillo Jr.

The automobile changed the face of the American West. It helped create metropolitan areas and suburbs, allowed people to pull up their roots and move, and after both World Wars I and II, automobiles helped create the dramatic population increase in Sunbelt cities like Albuquerque. In more remote areas, the automobile improved the feelings of loneliness experienced by those in isolated communities.

Henry Ford's Model T fueled the automobile age. The company's mass production techniques increased worker productivity and allowed Ford to sell more cars for less money. By 1927, Ford had sold over 15 million automobiles, more than all the other manufacturers combined. The demand for products used to build and maintain automobiles also resulted in new types of businesses, including auto dealerships and service stations.

The automobile industry also influenced the lives of women and youth. For the first time, young people felt free from the protective 'meddling' of their families, and saw in their "wheels" a mechanism for becoming more independent. Even 1950s slang was rooted in American car culture: hot rodders could "burn rubber," "drag," or go "cruisin' for a bruisin.'"

(rt) Governor John E. Miles and his 1941 Cadillac in front of Oden Motor, 312-324 N. 4th Street, 1942

The Brooks Collection. A Gift of Channell Graham.

PA1978.151.873

License plates, 1920s-1980s

Safe for a Sane Driver

La Bajada Hill was so steep that the 500-foot drop and 23 murderous switchbacks caused drivers of automobiles with gravity-fed tanks to ascend in reverse, or get pulled up the hill by mules. A warning sign installed by the highway department read, "This road is not fool proof, but safe for a sane driver."

"We heard a dull 'boom-boom' so I stopped and opened the back door and looked out ... and then I saw fire ... .A big truck had wrecked, hit the bridge and set it on fire." — Lee Marmon, Laguna, "Route 66 and Native Americans", 2009

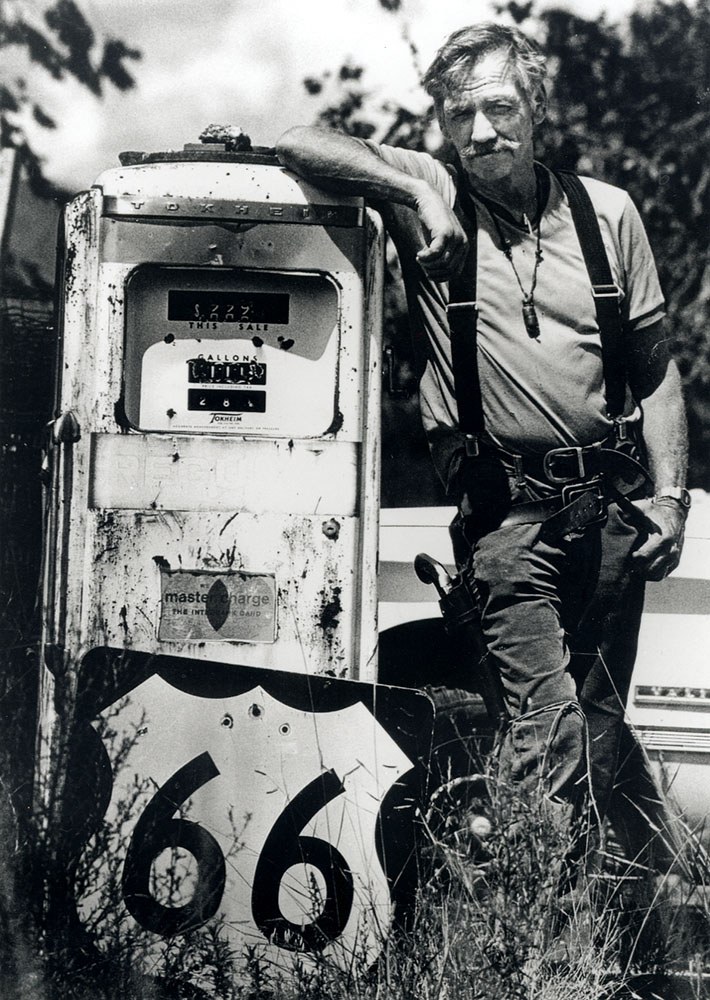

"Deadly 66" was yet another nickname ascribed to the Mother Road. Especially before segments of the highway were paved and expanded to four lanes, sections remained treacherous.

In the Southwest, drivers endured dust storms, tornados, extremes of heat and cold, snow and ice. Road obstacles included migrant hitchhikers, cattle and sheep, and other broken-down vehicles. Sometimes the road itself was the danger: Dead Man's Curve, a 180-degree curve in the highway near Mesita, New Mexico, has claimed the lives of countless drivers. In Arizona, one out of every six traffic deaths in 1956 was on "Camino de la Muerte" (Road of Death). Between Glenrio and Tucumcari, there were so many accidents in the 1960s that the route there became known as "Slaughter Lane."

Running out of gasoline or water in the middle of nowhere was a very real risk. Drivers depended on signage, road maps, travel guides, and especially service stations to keep their motors running. Gullible drivers were vulnerable to disreputable station attendants, who used dirty tricks to sell batteries and alternators. Service stations used fancy signage and captivating creatures to attract the attention of weary travelers.

"If you were driving through Tijeras Canyon in the old days, you had to honk your horn before going into a turn because there wasn't enough room for two cars ... .You had to be careful not to sideswipe someone." — Bob Audette, "Route 66: The Mother Road", 2001

Hairpin curves of La Bajada Hill, c. 1920

Gift of James and Betty Rutledge

PA1993.19. 15

"Stories of the Road" gallery

Courtesy Autry Museum of the American West, New Mexico History Museum, Steve Rider, and David Nufer

Minnequa water bag, 1940s-1950s

Pueblo Tent and Awning Co., Pueblo, Colorado

Canvas, rope

Courtesy Albuquerque Museum

Gift of Mrs. Roger Hartman

1999.76.3

Stories of the Road

"Singing Cowboy" Jules Alan's music paved the way for future cowboy artists Gene Autry and Roy Rogers in the 1930s.

"... Route 66 is people. That is what the road has always been about and why it remains active and relevant to this day." — author Michael Wallis, "Route 66, The Mother Road", 2001

What is it about traveling Route 66 that taps into human sentiment? Is it the hot summer air blasting through open car doors, inviting the pungent smell of steaming asphalt, or the sight of a brilliant-hued southwestern sunset? Is it the gut-wrenching remembrance of a forced flight from hard times, or the inspired hopefulness of a life started over in freedom?

Artist Andy Warhol did it, so did cowboy icon Roy Rogers, author Ernest Hemingway, and scientist/collector Frank Harlow. Each traveled the route for a purpose that ultimately changed their lives, and ours.

We all have our stories of the road. Enjoy the remembrances of our museum guests, and be sure to tell "your "story in the Route 66 Storybooth.

Bob Audette, c. 1988

Gift of Bob Audette

PA2000.20.3

Destination America

"Now truly you are in a fabulous land, for in this part of your trip you will pass ancient pueblos, volcanic lava flows, the Continental Divide, Indian Reservations, the Painted Desert, the Petrified Forest, and many Indian trading posts." — John Rittenhouse, "A Guide Book to Highway 66", 1946

The Great American Road Trip starts this way:

You gas up. Pack and load your luggage. Hit the highway and find your stride. Drive, eat, sleep, laugh, sing, play road games, sightsee, dream of the future. Find a place for the night, get a few hours' sleep. Wake to the smell of coffee, waffles and scrambled eggs, if you're lucky. Eat, then repeat. Or, put out your thumb and see where life takes you.

For every traveler on Route 66, there's been a way to draw them off of the road. Giant Muffler Men, towering Indian arrows, and concrete concoctions of every sort beckon from the distance. Billboards competed for driver attention, offering everything from shaving cream to camera film. Volcanic tubes of blue-green ice, rocks shaped like owls and elephants, trading posts pushing live buffalo and venomous vipers, and poster-painted teepees have demanded our attention, and still do.

(l-R) Red Ryder (Dave Saunders), Little Beaver (Arnold Vigil) and Monte Montana with horse at the entrance to the Fred Harman Cartoon Studio, Little Beavertown, c. 1961.

Gift of Vicky Dean Mayhew

PA1998.10.17

Sign, Jackrabbit Trading Post, after 1949

Wood, paint

Anonymous lender

Beyond the Hood

"Elvis Presley would come in from California through Gallup in his pink Cadillac and watch the lights of Albuquerque from the top of Nine Mile Hill. Everybody knew when he was coming, and we would watch him at the filling station." – Emma Moya, 2002

Hotels, 'auto camps,' 'tourist courts,' and 'motor lodges' used monstrous buildings, ingenious architecture, and brightly colored neon signage to attract overnight guests and get them to stop. The concept of the tourist court or motor lodge developed from increased travel after World War II, and the desire for travelers to have an inexpensive place to lodge overnight.

Albuquerque's railroad-era Mission style Alvarado Hotel, with its north façade located directly on Central Avenue, served both train and automobile travelers. The Franciscan, built in 1923 at Central Avenue and Second Street, was Albuquerque's first hotel designed to specifically attract automobile travelers. Its Pueblo Deco architecture and furnishings were major tourist attractions.

C.G. Wallace's De Anza Motor Lodge, built in 1938 in the Spanish-Pueblo Revival Style, sported a sign shaped like a Spanish conquistador's helmet in tribute to Spanish governor Juan Bautista De Anza, who secured peace for the Pueblos in the 1770s. The "tourist court" craze spawned entrepreneurs like Myron Robart, who founded the Franciscan Furniture Company to meet the needs of a burgeoning motel industry.

Sign from the Alvarado Hotel news stand, 1930s-40s

Wood, metal, paint

Museum purchase

2014.8.1

The Dog House Drive-In, 123 N. 10th Street, 1951

Albuquerque Progress Collection

Gift of Albuquerque National Bank

PA1980.186.794

Road Food

"I didn't ever want to live anyplace where you couldn't drive down the road and see drive-ins and giant ice cream cones and walk-in hot dogs and motel signs flashing." — Andy Warhol

The rise of the automobile in American culture heightened the demand for products such as steel and glass for travel-related services including roadside restaurants. "Mimetic" architecture and signage architecturally designed to imitate the kind of service being offered became popular all along the roadway, along with "Googie" style glass windows and angled facades. Owners of new restaurants have perpetuated the trend, much to the glee of today's travelers.

At the Big Texan in Amarillo, R.J. "Bob" Lee challenged tourists to down a 72-ounce steak for free, while Holbrook drivers are enticed to stop by a neon Dairy Queen ice cream sign. Regional road food favorites include green chile cheeseburgers, chicken enchiladas, fluffy sopaipillas dripping in honey, and frosty bottles of soda pop.

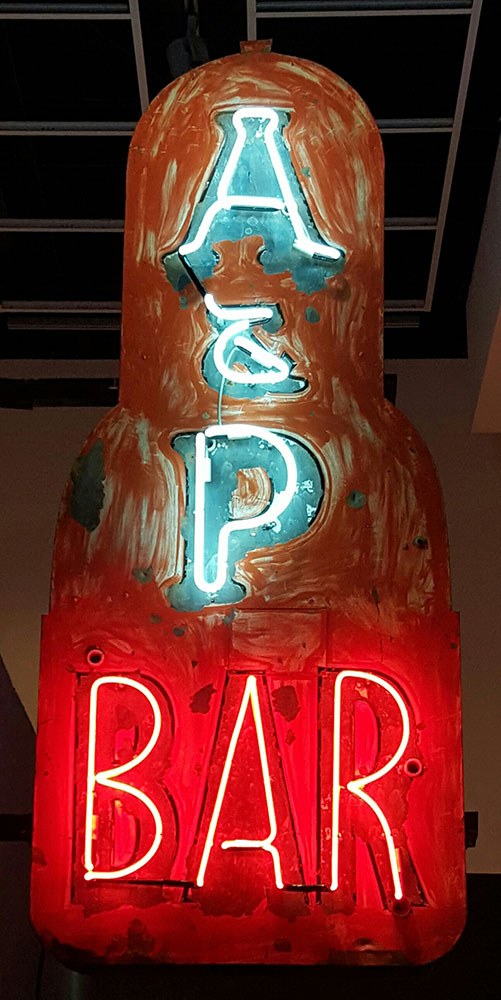

By the 1950s Albuquerque had a new nickname: The Neon City. For decades, Zeon Neon, Albuquerque Neon and others have manufactured signs for restaurants and businesses in our city. Neon has reached a new art form; the simple block letters of the 1920s and '30s have given way to complex color combinations, chasing lights, and animation.

"Iceberg Café", c. 1940

Gift of Fred Uranga

PA1996.48.1

Here It Is!

"John Yellowhorse told me ... his family lived out by Houck, Arizona, close to the highway. Their mom used to set up a loom on the edge of the road and weave little rugs. People would stop; they'd make a few bucks, and mom would say, "Would you like our kids to sing you a song in Navajo for a blessing for your trip?" And they'd sing a song with no meaning, and people would give them a nickel or something. Mom would save the nickels and buy clothes and shoes for school." — Terrence Moore, 2016

No road trip is complete without rest stops. Some drivers try their best to deadhead to their destination; others take their time — it's all about the experience. The kids ask, "Are we there yet?" while tourist traps attempt a delay via promises of lucite-embedded scorpions, cholla-wheeled chuck wagon lamps, and rattlesnake eggs.

Whether the trip was into Albuquerque – also known as "New Mexico's Downtown" — or down the road a bit, there were products to purchase and services to obtain. After World War II restrictions on goods were lifted, travelers could buy newly manufactured products made from metals, acrylics, and synthetic fabrics. Clothing lines expanded along with dress lengths and sleeve sizes. Within a three-mile strip of Central Avenue you could purchase Kodak film, a silver bolo tie, and a Western jacket for your trip.

The Route 66 experience is driven not only by nostalgia for the road and its architecture and material culture, but also by the interaction with people encountered along the way.

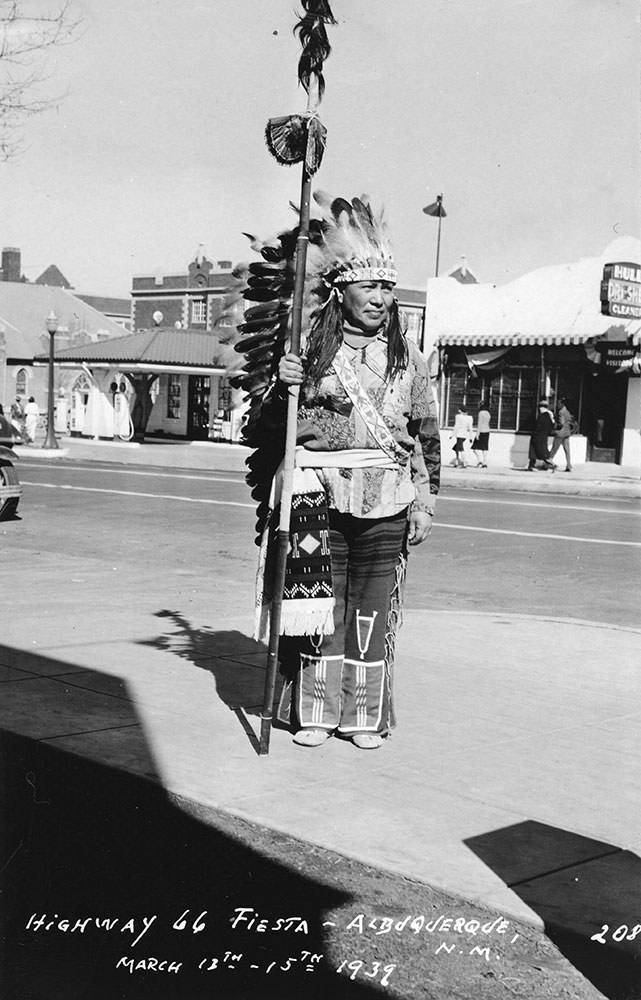

For many who trace the route an important part of the trip is the introduction to Native American culture, but too often the visitor experience extends only to the souvenir shops.

The people whose villages intersected the highway often felt disadvantaged by the tourist economy. Today, the Indian Arts and Crafts Act (amended 1990) protects the artistic traditions of Native people and prevents businesses from misrepresenting inventory as Native made.

Native American man at the Highway 66 Fiesta, Albuquerque, March 12-15, 1939

Gift of Jeff McDaniel

PA2007.17.2

Kurt's Camera Corral signs, 1990s

Southwest Outdoor Electric, Albuquerque

Glass, metal, neon

Gift of Jim Kubie

Road Rebels

"Now, you're either on the bus or off the bus. If you're on the bus, and you get left behind, then you'll find it again. If you're off the bus in the first place — then it won't make a damn."" — Ken Kesey, as quoted in Tom Wolfe, "The Electric Kool-aid Acid Test", 1968

By the 1960s, sections of Route 66 were in serious decline. Strip malls began to replace downtown shopping districts; out-of-town construction made possible by the automobile industry fueled new suburban developments. Travelers began to hate the main street traffic jams. The Eisenhower administration dealt the Mother Road a near-fatal blow by enacting the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, authorizing $25 billion to construct a 41,000-mile interstate highway system, ironically due to public demand for safer, faster transportation routes. Albuquerque's segment of Interstate 40 was completed in 1970.

By then, creative types were already waxing nostalgic about cross-country travel. Iconic Rebel poet Jack Kerouac's "On the Road" became the bible of the Beat Generation, championing the cause of the outsider, while poet Allen Ginsberg's "Howl "denounced American capitalism. Author and drug guru Ken Kesey followed suit, taking the Merry Pranksters along for a body-jarring road trip in their bouncy 1939 Harvester school bus, "Furthur", to celebrate the publication of "Sometimes a Great Notion" in New York. Filming a documentary along the way, Kesey invented memorable, enduring phrases like, "Do your thing," and "You're either on the bus or off the bus."

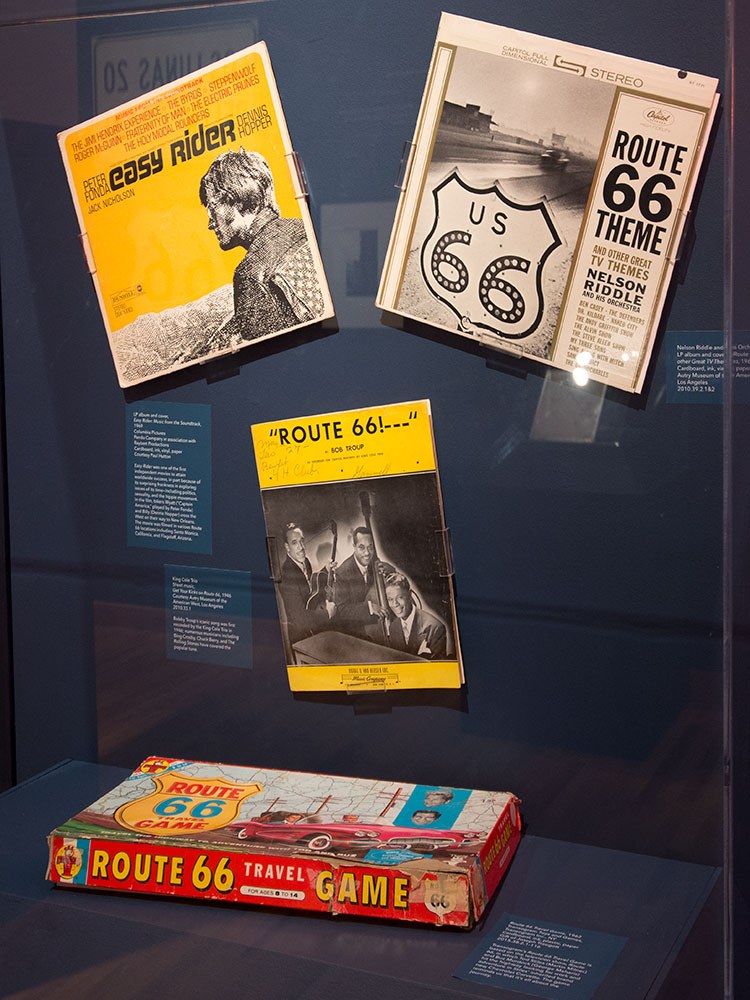

As Route 66 declined in the mid-20th century, its story merged with the theme of the road rebel in music, film and television. Bobby and Cynthia Troup conceived of "Get Your Kicks on Route 66" in 1946, driving from their Philadelphia home to St. Louis and then California via Route 66. By the 1960s the road rebel theme infiltrated film and television, bringing travel-hungry Americans the stories of defiant and often fatally flawed road warriors.

Souvenir vest, 1950s

Felt

Gift of Nancy Tucker

2007.68.6

Maisel's ash tray and bolo tie, 1930s-1970s

Silver, copper alloy, leather

Gift of Norman L. Sandfield

PC2012.16

Zuni, Navajo, and Pueblo jewelry, 19th-20th century

Silver, turquoise, shell heishe, turquoise, abalone, white clam shell, Hubbell beads, gray lip oyster, white and yellow shell, red glass, turquoise jaclas, spiny oyster

Gift of Eason Eige

2010.5

A&P Bar and Dispensary neon sign, late 1930s

Steel, paint, glass, neon, ceramic

Transfer, City of Albuquerque Planning Department

2015.2.2

Route 66 Revived

"The first time I drove on Route 66, what immediately jumped out at me was the way you could see the story of each town — its rich history and the way that the modern world had bypassed it. The spirit of Route 66 is in the details: every scratch on a fender, every curl of paint on a weathered billboard, every blade of grass growing up through a cracked street." — Disney/Pixar producer and director John Lasseter, "The Art of Cars", 2006

Construction of America's new cross-country highway system all but obliterated Route 66, officially decommissioned as a federal highway in 1985. Bypassed businesses were boarded up and abandoned, and properties within the right-of-way were demolished for highway construction. Barrels and barriers forced drivers off the Mother Road and onto the interstate. Old-timers like Angel Delgadillo, of Seligman, Arizona, fought to keep their grass-roots businesses afloat.

Although some businesses did not survive the transition from Route 66 to the Big I, many of Albuquerque's businesses have continued to thrive. Thanks to organizations like the Route 66 Alliance and the New Mexico Route 66 Association, visitors from around the world still trace the Mother Road's crumbling path, and artists continue to find inspiration in her mystique. Animated movies like Disney/Pixar's "Cars" (2006) help keep the thrill of Route 66 alive in the hearts of children — including the big ones, now grown up.

Through funding by the National Park Service, the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division and other organizations, numerous projects have documented what remains of Route 66 architecture, streetscapes, and signage. Government, non-profit and private funding has been instrumental in preserving Route 66 in New Mexico. Just a few preservation initiatives include the 2015 renovation of the Whiting Brothers service station in Moriarty by owner Sal Lucero, an upcoming renovation of Albuquerque's El Vado Court by Palindrome Communities, and a project by Anthea to restore the De Anza Motor Lodge. We all work together to preserve Route 66. Long live the Mother Road!

Road Rebels case with Route 66 record albums and travel game

Courtesy Autry Museum of the American West, Paul Hutton, and Joseph Traugott

Neon artist Robert Randazzo in his neon studio, 2016

Courtesy Robert Randazzo

Acknowledgements

"Route 66: Radiance, Rust, and Revival on the Mother Road" was organized by the Albuquerque Museum with assistance from the Albuquerque Museum Foundation, Lucia v.B. Batten Trust; Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Public Library, Special Collections Branch; American International Rattlesnake Museum; Anonymous lenders, Automobile Club of Southern California; Autry Museum of the American West; Ellen Babcock; Ed Boles; Cindy Carson, Mark Childs; City of Albuquerque Planning Department; Russ Davidson, Tom Elmhorst; EMP Museum, Seattle; Enchanted Vista Trailer Park; Kathy Flynn, National New Deal Preservation Association; Liz Fritzsche; Carlos Garcia; Getty Images; Kirk Gittings; Shellee Graham; Jay Hertz; Howard Greenberg Gallery; Frank Harlow, Katie Harlow, Heard Museum; Maryellen Hennessy; Paul Hutton; KNME-TV, Bill LaRue, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Louie's Rock-N-Reels; Robert McCubbin; Memphis Brooks Museum of Art; James Moore; Terrence Moore; National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; National Museum of Nuclear Science and History; New Mexico Council of Car Clubs; New Mexico Museum of Art, New Mexico History Museum, Fray Angelico Chávez History Library and Palace of the Governors Photoarchives; New Mexico State Records Center and Archives; New York Public Library; Frank Norris; David Nufer; Oklahoma State University Archives, Cyrus Avery Collection; Nicholas Potter Books; Philbrook Museum, Tulsa; Dorothy Rainosek, Steve Rider; Jim Ross; Sam Noble Museum, University of Oklahoma; San Jose State University, Steinbeck Center; Susan Sheehan Gallery; Bill Tondreau, Nancy Tucker; University Libraries, Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico; University of New Mexico Art Museum; Michael Wallis; Woody Guthrie Center; and the Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Copyright Albuquerque Museum, 2016 All Rights Reserved

Deborah C Slaney, Curator of History

May 14, 2016

El Vado Court neon sign, after 1937

Courtesy City of Albuquerque Planning Department